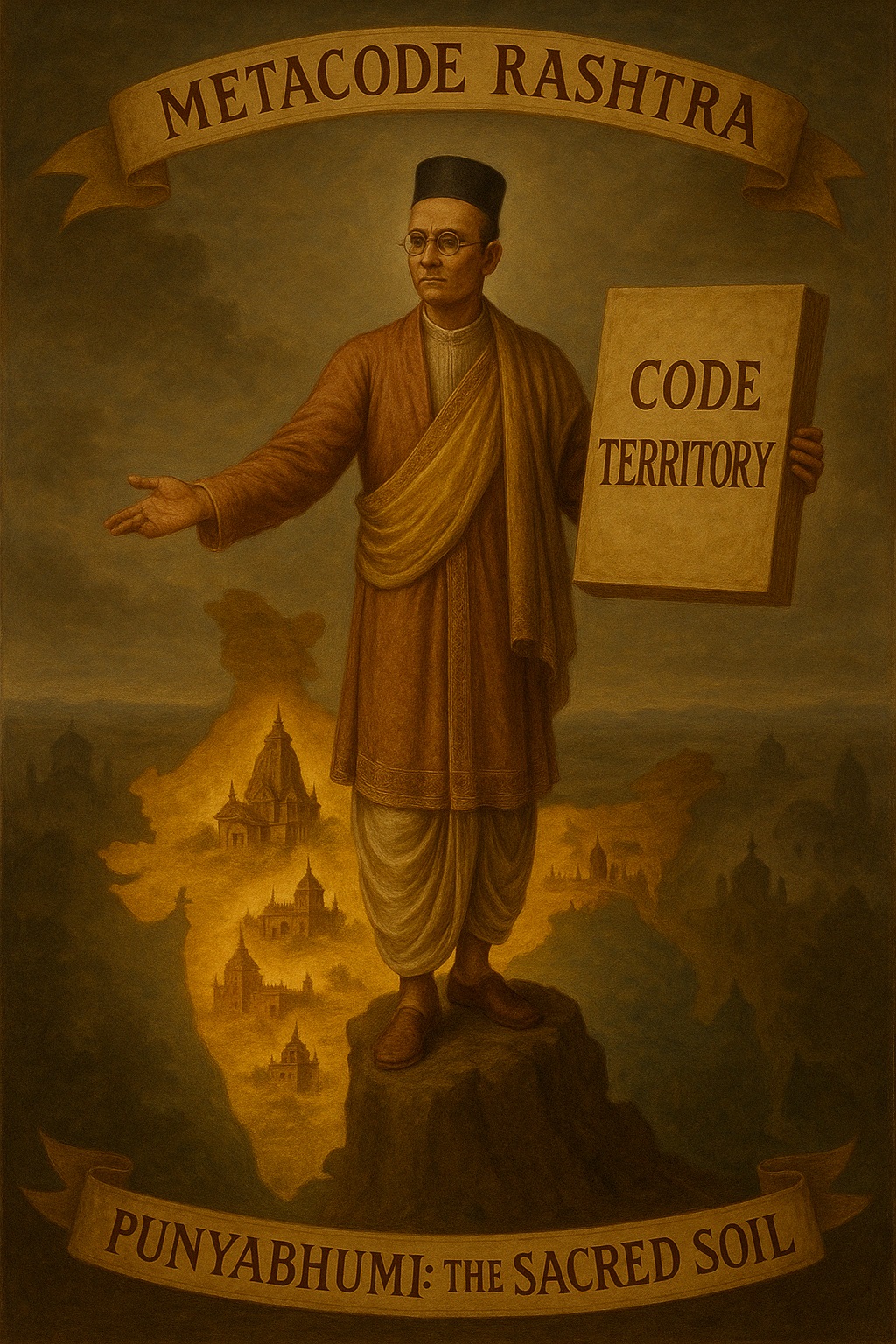

Savarkar’s coding of Hindutva; Metacode Rashtra, Part 4; Code Territory (3/6)

The concept of Punyabhumi, or “sacred land”, is central to Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s definition of the Hindu Rashtra. While he acknowledges the geographical and territorial aspect of the nation (Pitribhu), he further elevates it by embedding a religious dimension, defining it as a “sacred geographical space.” This dual foundation, both territorial and cultural-religious, forms the cornerstone of his ideology. It is significant to mention here that Savarkar understands Punyabhumi not just as a “holy land” but also as the land where one can earn merit through good works.

The Sacred Boundaries of Hindustan

Savarkar illustrates the sanctity of the land by referring to the four Dhamas – Badrikedar, Dwarka, Rameshwar, and Jagannath – which serve as religious and geographical markers of Hinduism. These sites delineate not just the spiritual sphere but also the territorial boundaries of the Hindu Rashtra. Thus, the Hindu nation is intrinsically linked to its land, making it both a fatherland and a holy land.

A fundamental tenet of Savarkar’s ideology is that only those who recognize India as their Punyabhumi can truly belong to the Hindu community. The very term Punyabhu conveys the idea that the land is where religious merits are accumulated through righteous actions. This conviction extends further, positioning service to the nation as the highest moral duty of Hindus.

Historical and Mythological Justification

The sacred nature of the Rashtra is reinforced by its deep-rooted connection to India’s mythical and historical past. Mythological events, central to Hindu tradition, are not merely cultural narratives but are interpreted as historical occurrences that justify the “sanctity of the land”. In the Hindutva framework, myths play a pivotal role in nation-building, serving as a unifying force that binds people to their homeland.

Savarkar envisions Hindus as the nucleus of a Universal World State. He links India’s cultural history to the broader evolution of human civilization, positioning it as the birthplace of significant religious movements, including Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. This idea reinforces the notion that India’s sacred geography has a universal significance, extending beyond national boundaries.

The Exclusive Nature of Punyabhumi

Savarkar makes a crucial distinction between Hindus and those whose sacred land lies beyond the Indian subcontinent. He asserts that Christians and Muslims, despite sharing India as their fatherland (Pitribhu), do not recognize it as their holy land (Punyabhumi). Their spiritual and historical loyalties lie elsewhere – in Palestine and Arabia—which divides their allegiance. This distinction serves as a basis for his exclusionary definition of Hindutva, where national identity is deeply intertwined with religious and cultural unity. According to Savarkar, while India (Hindustan) is the ancestral land (Pitribhu) for Indian Muslims and Christians, just as it is for any other Hindu, it is not considered their holy land (Punyabhu). Their sacred places are located in Arabia or Palestine. Their religious stories, saints, beliefs, and revered figures originate from outside of India. As a result, their names and perspectives carry a foreign influence. Therefore, their loyalty is divided. (Savarkar 1999:70f. He justifies the relativization of the geographical reference point as follows: “A person, who „has not adopted our culture and our history, inherited our blood and has come to look upon our land not only as the land of his love but even of his worship, he cannot get himself incorporated into the Hindu fold“ (Savarkar 1989:84).

Nation-Building: A Union of Sacred and Secular

Savarkar’s vision of nationhood extends beyond mere territorial unity. He argues that a nation cannot be built purely on geographical commonality – it must also be rooted in cultural and spiritual homogeneity. Thus, the coding of geographical space through both profane and sacred elements is essential. A true national unity, in Savarkar’s view, arises from the fusion of common religion, language, culture, and a shared sense of a sacred homeland.

His vision for a magnificent and splendid India is one where Hindus actively work towards the advancement of their civilization, enriching humanity while preserving and expanding their cultural heritage. Savarkar urges his followers to continue their colonial mission to create a grand and glorious India. He encourages them to build a Mahabharat (referencing the epic, implying a great endeavor) that fully utilizes their skills and potential. He calls for them to employ all the beneficial virtues and qualities of their civilization to serve humanity. He envisions them enriching all of humankind with their virtues while simultaneously serving their land and people by embracing and disseminating helpful and true knowledge. (Savarkar 1999:74)

Territory and Spirituality: A United Vision

Savarkar sought to establish the Indian subcontinent as the primary unifying factor for Hindus, blending the material and spiritual. As German scholar Jakob Rösel described it, this involved a “superficial territorialization of a faith and a background sacralization of a territory” (Rösel 350). Crucially, Savarkar rejected the idea of a nation based solely on geographical boundaries. He believed that nation-building required a conscious effort to unite diverse peoples through shared religion, language, culture, fatherland, and holy land. (Savarkar 2007:236). In essence, Savarkar’s Punyabhumi is more than just a place on a map; it’s a spiritual and cultural heartland, a cornerstone of his vision for a unified Hindu nation.

Final Thoughts

The idea of Punyabhumi is fundamental to Savarkar’s Hindutva, reinforcing the inseparable link between land, religion, and identity. By defining the Hindu nation through both territorial and spiritual elements, he establishes a framework where national unity is achieved not merely through political means but through a shared religious and cultural consciousness. This notion remains central to Hindutva discourse today, continuing to shape discussions on identity, belonging, and the concept of nationhood in India.

What are your thoughts on Savarkar’s idea of Punyabhumi as a sacred land? Do you think religion and territory should be intertwined in defining a nation? Savarkar distinguished between Hindus and non-Hindus based on their sacred lands. What’s your perspective on the idea of spiritual loyalty to a land? Do you think the fusion of sacred and secular elements is essential for national unity? Can a nation be united solely on geographical commonality? Share your perspectives in the comments below!

Sources:

KLIMKEIT, Hans-Joachim. 1981. Der politische Hinduismus. Indische Denker zwischen religiöser Reform und politischen Erwachen. Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden.

RÖSEL, Jakob. 1994. “Die indische Demokratie unter der Herausforderung des Hindunationalismus“, in: W. Jäger, H. O. Mühleisen, H. O. Veen (Hrsg.), Republik und Dritte Welt; Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag Dieter Oberndörfers, Paderborn pp. 349-359;

ROTHERMUND, Dietmar. 2003. „Asien und die Globalisierung in historischer Perspektive“. Referat im Rahmen der Tagung: Asien in der Globalisierung Weingartener Asiengespräche 2003. Akademie der Diözese Rottenburg-Stuttgart, Weingarten/Oberschwaben, 31.1.-2.2.2003

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 2007. Hindu Rashtra Darshan. Bharat Bhushan. Abhishek Publications: New Delhi.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1999. Hindutva: Who is a Hindu. Seventh Edition. Swatantryaveer Savarkar Rashtriya Smarak: Mumbai.

PHAKE, Sudhir/PURANDARE, B. M. and Bindumadhav JOSHI. (Eds.). 1989. Savarkar. Savarkar Darshan Pratishtnah (Trust): (Bombay) Mumbai.

Leave a Reply