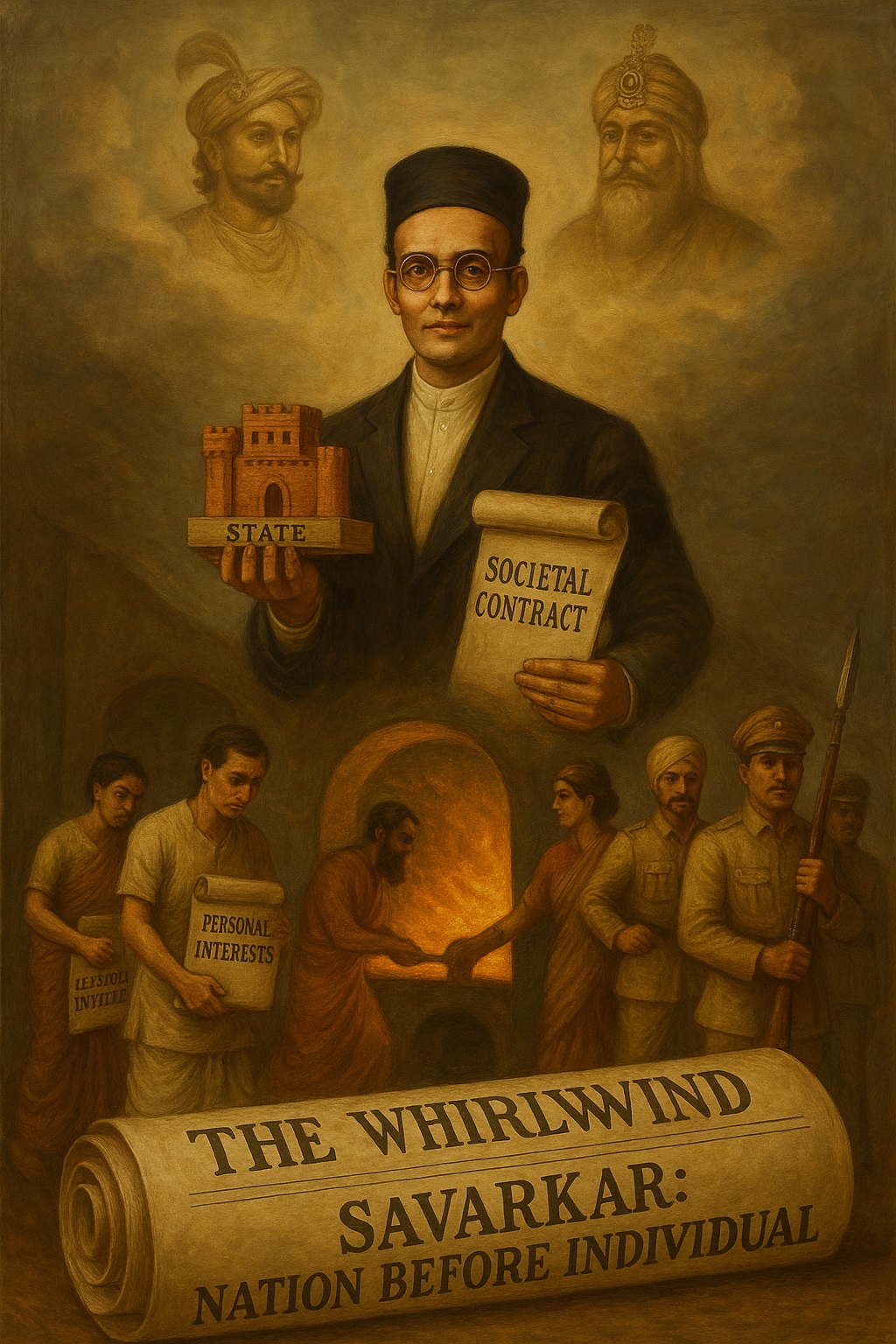

Political Dimension of Hindutva, Part 5

In his political thought, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar presents a vision that is deeply entwined with the idea of collective identity and the supremacy of the nation. His ideas reflect the notion that individual interests must be subordinated to the common good, especially in the context of a nation striving to preserve its sociocultural, political, and economic existence. This thought is central to his interpretation of the relationship between the individual, the community, and the state.

The Basis of Savarkar’s Thought: Conflict, Hierarchy, and the Scarcity of Resources

Savarkar’s framework of understanding sociopolitical and cultural life revolves around the concept of conflict. He argues that all societies are structured through hierarchies of dominance and subordination, with people constantly striving for scarce resources like power, prestige, and wealth. This constant struggle is at the heart of his vision for governance, where the state serves not just as an institution but as a mechanism to ensure the survival and flourishing of the Hindu community.

One of the most prominent ideas in his thought is the need for a unified political community, which he describes as an idealized state founded upon “absolute idealism.” According to Savarkar, the personal interests of individuals must be placed behind the greater goals of the nation and the state. For him, the ideal governance system is one that is supported by a nation, in which each individual sacrifices their personal desires for the collective well-being.

The Marathas and Sikhs: Historical Examples of the State Ideal

Savarkar points to two examples in Indian history that come closest to realizing this ideal: the Marathas and, to a lesser extent, the Sikhs. The Maratha empire is portrayed as a successful and remarkable example of this national ideal, where a sense of unity and common purpose allowed for the consolidation of power. The Sikhs, while also forming a confederated state, did not achieve the same territorial scope or continuity as the Marathas but are still seen by Savarkar as an example of a “confederated Hindu power.”

However, the question remains: why did these communities not fully embody Savarkar’s vision? He argues that there was no consensus among the Hindu (sub-)nations regarding the formation of a unified political system. The Marathas, in particular, faced the challenge of consolidating a pan-Hindu empire, and Savarkar recognizes that in the absence of a collective patriotism, coercion was often necessary.

Coercion and the Subordination of Individuals to the Nation

Savarkar’s thought takes a more radical turn when he suggests that, in the absence of consensus, political coercion is justified to ensure unity and preserve the nation. The leadership of the Marathas, in Savarkar’s view, had the right to integrate other Hindu states into a unified system, even if this required force. This idea is linked to Savarkar’s utilitarian perspective, where the ultimate goal is the greatest happiness for the greatest number, even if this means sacrificing the interests of a few individuals.

For Savarkar, the success of the Hindu nation depends on the willingness of its leaders and citizens to subordinate themselves to a higher political power. The concept of “might is right” underpins this view, as it posits that those in power, whether through force or moral leadership, have the right to lead the community toward national unity and strength.

The Marathas and the Question of Persuasion versus Force

Although Savarkar acknowledges the importance of persuasion, he believes that it was highly unlikely that the Marathas could have formed a unified Hindu empire through voluntary cooperation alone. In his view, the fragmented nature of Hindu society at the time – divided by various regional, cultural, and religious differences – meant that a sense of patriotic unity was not likely to emerge spontaneously. Instead, he believed that the Marathas had to use force to unify the Hindu states and communities, something that was common in the history of India.

Historical Continuity and the Need for Leadership

Savarkar’s argument is deeply rooted in historical continuity. He emphasizes that the Marathas were not the only ones to use coercion and violence to unite Hindu kingdoms; similar patterns had been observed throughout Indian history. This forced integration, he claims, is a natural part of nation-building processes, especially when there is no widespread recognition of the need for unity. He compares this process to the unification of Italy and Germany in Europe, where smaller states had to be brought together under a larger, more powerful state.

The State as the Ultimate Arbiter of Societal Goals

Savarkar’s vision of the state is far from liberal. The state, in his view, is not just a protector of individual rights and freedoms but also the ultimate arbiter of societal goals. These goals, however, are defined according to Savarkar’s own conception of Hindu identity and nationalism. The state, therefore, has the right to intervene in every aspect of life, from education to moral behavior, to ensure that the nation’s goals are realized.

His emphasis on a strong, centralized state reflects his rejection of liberal ideals, particularly the idea that the state should be neutral towards different segments of society. Instead, Savarkar argues that the state must ensure the unity of the Hindu community, even if this means restricting individual freedoms for the greater good.

Final Thoughts – A Vision of Coercion for the Greater Good

Savarkar’s political philosophy places the collective good of the Hindu community above individual rights. His vision of leadership, national unity, and the role of the state in enforcing this unity challenges liberal ideas of governance, placing a premium on the strength and cohesion of the nation. His ideas raise important questions about the balance between individual liberty and the demands of the community, especially in the context of nation-building and cultural preservation.

In the end, Savarkar’s thought suggests that in times of crisis, coercion and violence may be necessary to preserve the nation, a stance that remains deeply controversial but is central to his interpretation of India’s political future. As we examine his ideas today, they serve as a potent reminder of the complexities inherent in the relationship between the individual, the state, and the community.

Sources:

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1971. Six glorious (golden) epochs of Indian history. Savarkar Sadan: Bombay. 1971.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 2007. Hindu Rashtra Darshan. Bharat Bhushan. Abhishek Publications: New Delhi.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1971. Hindu-Pad-Padashahi or a review of the Hindu empire of Maharashtra. Bharti Sahitya Sadan (Fourth Edition): New Delhi.

Leave a Reply