As soon as Vinayak Damodar Savarkar established himself in London, he founded the Free India Society in 1906. The organization became a crucible of revolutionary thought and action at the heart of the British Empire. Publicly open but ideologically radical, the Society was modeled after Giuseppe Mazzini’s Young Italy and served as the overseas face of Savarkar’s earlier underground movement, Abhinav Bharat.

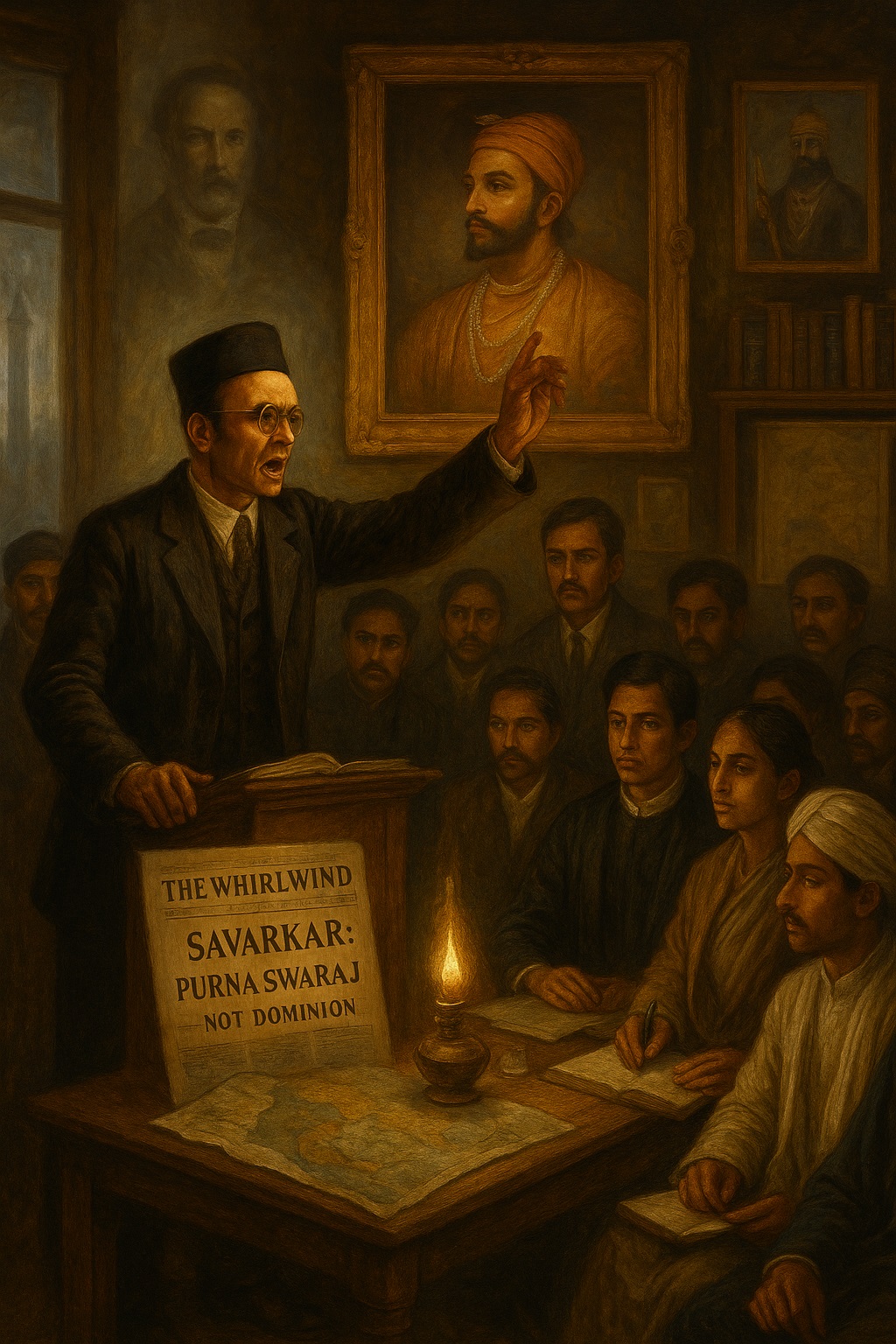

The Free India Society was not merely a debating club of idealistic students – it was a revolutionary hub. Its aim was to unite and transform Indian youth abroad into patriots and martyrs. In this capacity, the Society also functioned as a recruiting platform for Abhinav Bharat. Weekly Sunday meetings, often held at India House in Highgate, North London, became electrifying events, brimming with political debate, historical lectures, and celebrations of Indian cultural and historical figures such as Shivaji, Guru Gobind Singh, and the heroes of 1857—a year Savarkar called the “First War of Indian Independence.”

The Society’s goals were radical and uncompromising, aimed at stirring and spreading patriotic and anti-colonial sentiment. Unlike the Indian National Congress, which at the time still entertained ideas of gradual reform and dominion status, Savarkar’s vision was Purna Swaraj – complete independence. His lectures championed armed struggle as a legitimate path, drawing parallels with revolutionary movements in Italy (Risorgimento), Ireland, Russia, and America. The emphasis was always on direct action: peaceful evolution was acceptable, but peaceful revolution, he argued, was meaningless.

The Society attracted Indian students from universities across Britain – Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, and Manchester. These young minds were not merely educated in nationalist ideology; they were trained in revolutionary methods. Savarkar and his associates arranged instruction in explosives, distributed radical literature, and even plotted coordinated actions against the British Empire. Among their more ambitious plans was a proposed sabotage of the Suez Canal, devised with the help of Egyptian nationalists, to disrupt British control in the event of an Indian uprising.

One of the Free India Society’s most publicized moments came with the involvement of Madan Lal Dhingra, a member deeply influenced by Savarkar’s teachings. Dhingra’s assassination of British official Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie in 1909 shocked the British establishment and signaled the seriousness of this overseas revolutionary movement. Though condemned by many moderates, the act resonated as a powerful symbol of colonial resistance.

The Society also worked to foster pan-Indian solidarity. People from all provinces – Punjab, Bengal, Madras, Bombay – and from diverse faiths including Hindus, Muslims, Parsis, and Jews came together under its banner. Celebrations of Indian festivals and anniversaries served to build unity and pride in a shared heritage. One such event, the 1908 commemoration of Guru Gobind Singh at Caxton Hall, featured speeches by towering nationalists like Lala Lajpat Rai and Bipin Chandra Pal.

Savarkar’s influence extended through literature as well. His book The Indian War of Independence, 1857 was banned in India but widely circulated in secret. He also contributed to revolutionary journals like Talwar, edited by Virendranath Chattopadhyay, and cultivated ties with other international revolutionaries and intellectuals.

The Free India Society eventually faced inevitable suppression. With Savarkar’s arrest in 1910 and his subsequent deportation to India, the Society’s activities dwindled. Yet its legacy endured. It had radicalized a generation, drawn global attention to the Indian cause, and laid the ideological groundwork for future organizations like the Ghadar Party and the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association. Key members included Madan Lal Dhingra (the student who assassinated Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie), Shyamji Krishnavarma (founder of India House and crucial supporter of the Society), V.V.S. Aiyar (a close associate of Savarkar and a key revolutionary figure), Lala Har Dayal (a prominent nationalist associated with the Society during his time in London), and Madame Bhikaiji Cama (a staunch nationalist who supported revolutionary activities in London and Paris), among many others.

More than a footnote in India’s freedom movement, the Free India Society was a thunderclap – brief, intense, and transformative. It was not merely a gathering of dissidents; it was, as Savarkar intended, the heartbeat of a future revolution.

What are your thoughts on the Free Indian Society and its role in India’s struggle for Independence? Share your insights in the comments below!

Sources:

GODBOLE, Vasudev Shankar. 2004. Rationalism of Veer Savarkar. Itihas Patrika Prashan: Thane/Mumbai.

KEER, Dhananjay. 1988. Veer Savarkar. Third Edition. (Second Edition: 1966). Popular Prakashan: Bombay (Mumbai).

PINCINCE, John. 2007. On the Verge of Hindutva: V.D. Savarkar, Revolutionary, Convict, Ideologue, c. 1905–1924. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of Hawai‘i (at Mānoa) in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History.

SAMPATH, Vikram. 2019. Savarkar (Part 1). Echoes from a forgotten past. 1883-1924. Penguin Random House India: Gurgaon.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1993. Inside the enemy camp. Veer Savarkar Prakashan: Mumbai.

SRIVASTAVA, Harindra. 1983. Five stormy years: Savarkar in London (1906-1911) – A centenary salute to V.D. Savarkar. Allied: New Delhi.

Leave a Reply