Savarkar’s Struggle Against Untouchability, Part II

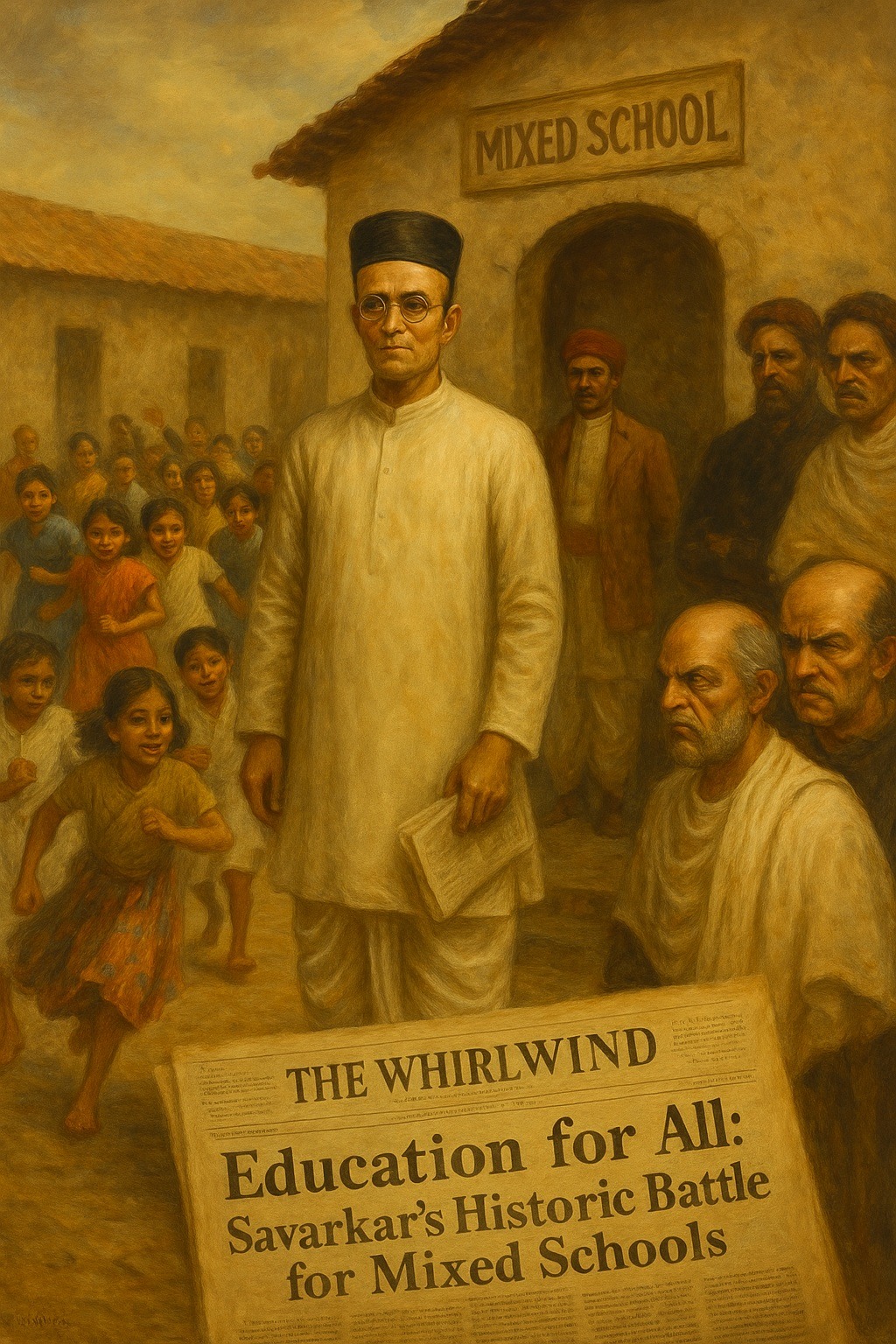

Among the many aspects of Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar’s reformist thought, his campaign against untouchability stands out as a crucial yet often neglected chapter. During his confinement in Ratnagiri, Savarkar directed his intellectual and organisational energy toward addressing what he regarded as one of the gravest internal weaknesses of Hindu society. His efforts to establish “mixed schools” – educational institutions open to children of all castes – represent a defining phase in his broader programme of social reconstruction.

The Educational Divide in Colonial India

Under British colonial rule, the hierarchical caste structure remained one of the most persistent barriers to education in India. The so-called “untouchables,” or members of the ‘Depressed Classes’, were systematically excluded from access to learning, both by custom and by institutional practice.

Although colonial administrators occasionally introduced policies aimed at widening educational opportunities – such as fee exemptions, scholarships, and the formal declaration of open admission to state schools – these measures rarely achieved their intended outcomes. The entrenched social order proved resilient. In practice, local elites often subverted such reforms through social pressure and boycotts.

Even when children from lower castes were admitted, discrimination was overt. They were made to sit apart from other pupils, sometimes near the doorway or even outside the classroom altogether. Parents of upper-caste students frequently objected to the presence of “untouchable” children, forcing administrators to maintain segregation. In extreme cases, entire schools were abandoned to prevent the mingling of castes.

Thus, despite the appearance of progressive legislation, educational institutions remained a reflection of caste hierarchy rather than a challenge to it.

Savarkar’s Vision: Education as an Instrument of Social Reform

Savarkar regarded education as a primary means of dissolving social prejudices. He argued that if children of different castes were educated together from an early age, they would naturally develop mutual respect and a sense of shared identity. Such an environment, he believed, would prevent the internalisation of caste-based hierarchies that adults often accepted as immutable.

To Savarkar, the struggle against untouchability could not be confined to moral exhortation or religious reinterpretation; it required structural reform. Education, by shaping the moral and intellectual foundations of society, offered the most direct route to such transformation.

In pursuit of this goal, Savarkar employed a dual strategy:

- Public Advocacy: Through the local press and various journals, he advanced arguments in favour of mixed schools. His writings combined moral reasoning with pragmatic nationalism—asserting that a society divided by caste could neither achieve nor sustain national unity.

- Community Engagement: Savarkar worked directly with local officials, educators, and civic leaders to overcome resistance. He raised funds for school supplies, books, and clothing to ensure that children from disadvantaged backgrounds could attend without financial impediments.

The Establishment of Mixed Schools in Ratnagiri

Despite significant opposition from orthodox circles, Savarkar’s persistent efforts led to tangible results. With the cooperation of sympathetic administrators and reform-minded citizens, mixed schools were established in Ratnagiri. These institutions served as early experiments in educational integration, where caste identity was deliberately set aside in favour of shared learning.

Their establishment marked an important precedent in the broader movement for social reform in colonial India. Within these classrooms, the act of learning together became a subtle yet powerful form of resistance against centuries of social segregation.

Savarkar’s initiative also provided a model for later reform efforts elsewhere in India, illustrating that societal transformation could be achieved through practical, community-based measures rather than solely through political agitation.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Savarkar’s campaign for mixed schools must be understood as part of his comprehensive vision for Hindu social consolidation (Hindu Sanghatan). For him, equality and unity were prerequisites for collective strength. Without internal cohesion, he argued, the Hindu community would remain vulnerable both to foreign domination and to moral decay.

His educational reforms were therefore both social and political in nature. They sought not merely to alleviate the condition of the oppressed but to reconstruct the ethical and cultural fabric of the nation.

Although the long-term impact of his initiatives in Ratnagiri was limited by the scale of his confinement, their symbolic significance was profound. They demonstrated that entrenched hierarchies could be challenged through deliberate, organised reform grounded in reason, empathy, and civic responsibility.

Final Thoughts

Savarkar’s advocacy of mixed schools represents a significant contribution to the history of Indian social reform. His approach combined intellectual clarity, strategic action, and a deep understanding of the psychological roots of caste prejudice.

By situating education at the centre of his reform agenda, Savarkar sought to create conditions for a new moral order—one in which equality was not an abstract ideal but a lived social reality. His efforts in Ratnagiri remind us that meaningful progress requires not only legislative change but also the cultivation of conscience through knowledge.

In this sense, the classroom became for Savarkar both a symbol and an instrument of national awakening.

💭 What do you think? How did Savarkar’s campaign for mixed schools challenge both colonial and traditional Hindu social structures? To what extent can Savarkar’s emphasis on education as a tool for social reform be compared to the approaches of other reformers such as Jyotiba Phule or B.R. Ambedkar? In what ways did Savarkar’s ideas on inclusive education anticipate later constitutional commitments to equality in independent India? Could Savarkar’s Ratnagiri experiment with mixed schools be interpreted as a form of “grassroots nationalism” rather than merely social activism? How might the concept of Hindu Sanghatan be understood in relation to Savarkar’s efforts to integrate caste groups through shared education? What obstacles continue to hinder educational equality in India today, and how might Savarkar’s methods of reform remain relevant in addressing them? How do we assess the legacy of Savarkar’s social reform initiatives in the broader context of his political and ideological evolution?

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

GODBOLE, Vasudev Shankar. 2004. Rationalism of Veer Savarkar. Itihas Patrika Prashan: Thane/Mumbai.

KELKAR, B. K. 1989. „Savarkar: A Thee-dimensional view“, in PHAKE, Sudhir/PURANDARE, B. M. and Bindumadhav JOSHI. (Eds.). 1989. Savarkar. Savarkar Darshan Pratishtnah (Trust): (Bombay) Mumbai, 42-60.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1971. Six glorious (golden) epochs of Indian history. Savarkar Sadan: Bombay. 1971.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1924. An Echo from Andamans. Vishvanath Vinayak Kelkar: Nagpur, in GROVER, Verinder. 1998. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar: A biography of his vision and ideas. Deep and Deep: Publications: New Delhi.

VARMA, Vishwanath Prasad. 1985. Modern Indian Political Thought. Volume II. 8. Ed. Lakshmi Narain Agarwal: Agra, 386-391.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2010. Savarkar’s Strategic Agnosticism. A compilation of his political and economic worldview, in Heidelberg Papers in South Asian Comparative Politics (HPSACP), No. 51, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2009. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar und sein Hindutva-Konzept. Die Konstruktion einer kollektiven Identität in Indien [“Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his concept of Hindutva: The construction of a collective identity in India.”]. Online Dissertation: Heidelberg University: Heidelberg.

Leave a Reply