In the battle to eliminate social evils, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar viewed the institution of community eating—or inter-caste dining—as a powerful weapon. This reform was seen by him as essential for dismantling the deeply entrenched barriers of the caste system and addressing the discrimination faced by Untouchables in Hindu society. The caste system, with its rigid restrictions on food sharing, was a major obstacle to the social unity Savarkar envisioned. He believed that the taboos surrounding who could eat with whom and what food could be consumed from whose hands were not merely cultural practices—they were significant sources of social division and caste-based oppression.

The Role of Food in Social Division

Savarkar pointed out that the caste-based restrictions on food were integral to maintaining the hierarchical structures of Hindu society. These rules were not just customs—they were the “glue” that held the caste system together, and its enforcement was the “life force” of Hindu orthodoxy. The prohibitions on eating together across castes were so deeply ingrained that they shaped every aspect of social interactions. In fact, the very idea of people from opposite ends of the caste spectrum eating together was an unimaginable transgression for many, even among high-caste Hindus.

Savarkar was keenly aware of the immense social control these food-related restrictions wielded. The majority of the Hindu population at the time not only adhered to these rules but also believed that violating them was a transgression of religious and moral codes. For Savarkar, breaking this cycle was crucial for social reform.

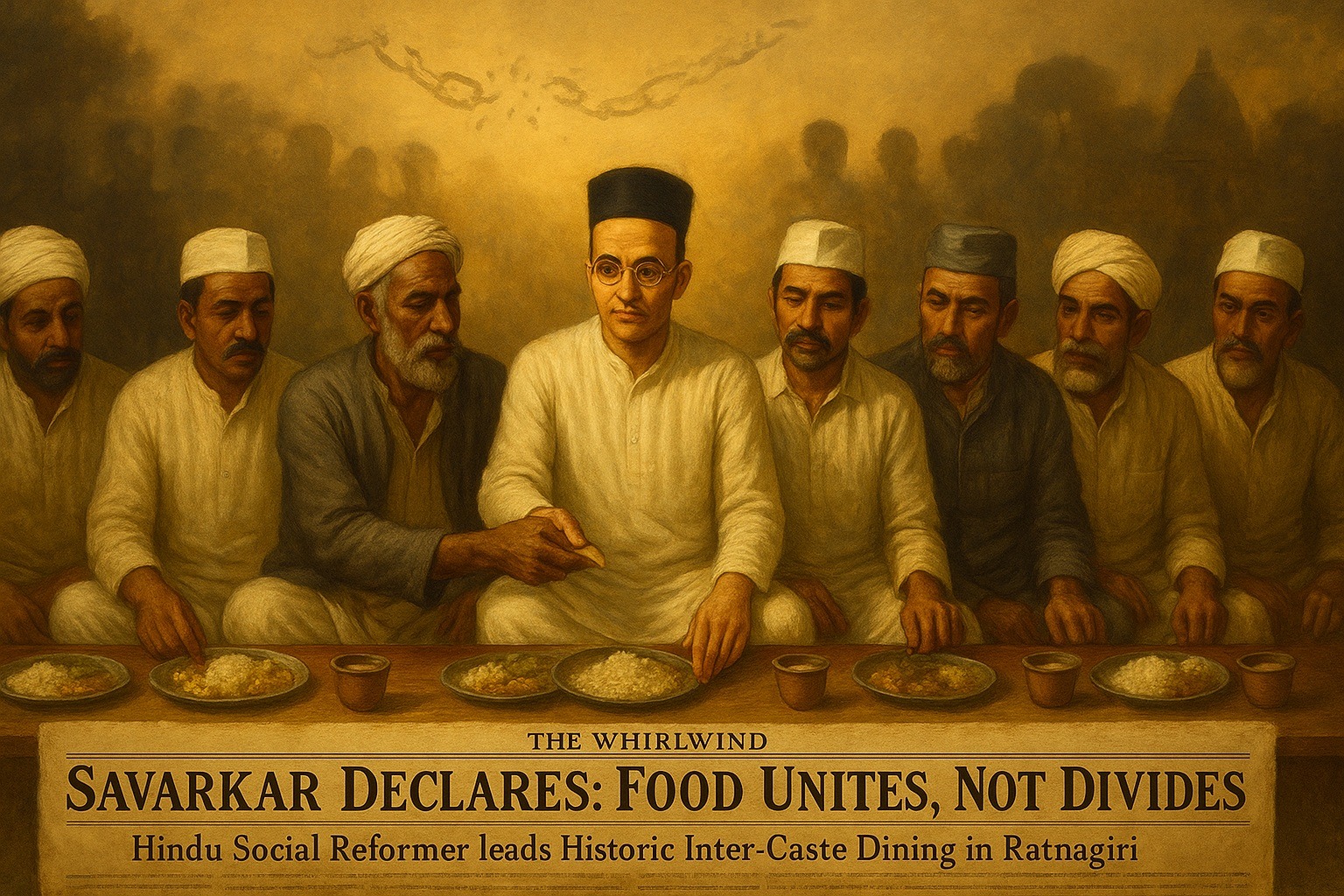

The Sahbhoj Movement: A Revolutionary Approach to Inter-Caste Dining

Savarkar’s bold social reform in the town of Ratnagiri introduced the concept of “Sahbhoj” or inter-caste meals, where Hindus of all castes, including Untouchables, could dine together. This initiative, organized on Sundays (Suryanarayam Divas), aimed to challenge the existing social norms and encourage unity through communal dining. To promote this new idea, Savarkar organized a series of lectures and seminars throughout the Ratnagiri district. His message was clear: “Eat with everyone and eat anything that is health-wise appropriate and clean, that which does not rob anyone of their religion.”

Savarkar’s focus was on hygiene, not religion. He argued that food choices should be based on health and cleanliness, not religious taboos. As he put it, “Remember, the origin of religion is not a dish or the stomach, but the heart, the soul, and the blood.” In his view, the act of sharing a meal should transcend caste and religious differences and be rooted in basic principles of health and human dignity.

Strong Opposition and Savarkar’s Resilience

The introduction of “community eating” met with strong opposition from several quarters, even among Savarkar’s own supporters. Many followers of the Hindu Mahasabha, while agreeing with Savarkar’s anti-Untouchability stance, found the idea of inter-caste dining too radical and potentially divisive. They feared that such initiatives might provoke social unrest and complicate political matters. Gandhi, the towering figure of the Indian independence movement, also voiced opposition. In November 1932, he famously stated that activities like “community eating” and “mixed marriages” were not necessary for the abolition of Untouchability and could create unnecessary obstacles to social harmony.

Despite this resistance, Savarkar remained steadfast in his vision. He took a gradual approach, organizing inter-caste meals whenever possible, and even published the names of participants in local newspapers to encourage more people to join the cause. His efforts bore fruit, as evidenced by an article in the Times of India on December 9, 1930, which acknowledged Savarkar as an inspiration for the reformers in Ratnagiri advocating for the end of caste-based discrimination.

The Lasting Impact of Savarkar’s Efforts

Savarkar’s campaign to abolish the restrictions on community eating was a landmark moment in the struggle for social justice in India. His Sahbhoj initiative served as a catalyst for broader social reforms and helped disrupt the rigid social order of caste. While the opposition was formidable, the significance of Savarkar’s work cannot be understated. It not only sparked conversations about the need for social equality but also ignited a movement that challenged the entrenched orthodoxy and caste-based discrimination.

In the end, Savarkar’s program for community eating, despite facing opposition, played a key role in advancing the cause of social reform. His work in Ratnagiri marked a turning point, helping to destabilize the caste system’s grip on society. The inter-caste meals he organized were more than just symbolic gestures—they were a practical means of breaking down the barriers that separated people on the basis of caste, contributing to the larger struggle for a more equitable and unified Indian society.

Savarkar’s efforts to abolish caste-based food restrictions left a lasting legacy, inspiring future generations of reformers to continue fighting for a society where everyone, regardless of caste or religion, could share a meal together in dignity and equality.

💭 What do you think?

Do you think breaking food-related taboos is still necessary to challenge caste discrimination today? Why or why not? How do you view the role of shared meals in building social unity across communities and identities? Can social reform succeed without challenging deeply rooted cultural and religious customs? Do you agree with Gandhi’s argument that community eating was unnecessary for ending untouchability, or was Savarkar’s approach essential? What obstacles still prevent full social integration across caste or cultural lines in contemporary India?

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

GODBOLE, Vasudev Shankar. 2004. Rationalism of Veer Savarkar. Itihas Patrika Prashan: Thane/Mumbai.

KEER, Dhananjay. 1988. Veer Savarkar. Third Edition. (Second Edition: 1966). Popular Prakashan: Bombay (Mumbai).

KELKAR, B. K. 1989. „Harbinger of Hindu Social Revolution“, in SWATANTRYAVEER SAVARKAR RASHTRIYA SMARAK. 1989. Smarak Inauguration. 28 May 1989. Festschrift. Swatantryaveer Savarkar Rashtriya Smarak: Bombay (Mumbai), 49-51.

PHADTARE, T. C. 1975. Social and Political Thought of Shri V.D. Savarkar. A Thesis submitted to the Marathwada University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Unpublished: Aurangabad.

SAMPATH, Vikram. 2019. Savarkar (Part 1). Echoes from a forgotten past. 1883-1924.Penguin Random House India: Gurgaon.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2010. Savarkar’s Strategic Agnosticism. A compilation of his political and economic worldview, in Heidelberg Papers in South Asian Comparative Politics (HPSACP), No. 51, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2009. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar und sein Hindutva-Konzept. Die Konstruktion einer kollektiven Identität in Indien [“Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his concept of Hindutva: The construction of a collective identity in India.”]. Online Dissertation: Heidelberg University: Heidelberg.

Leave a Reply