When we think of Ganesh Chaturthi (Ganeshotsava), the name of Bal Gangadhar (Lokmanya) Tilak often comes first. In the 1890s, Tilak had transformed a private household ritual into a public celebration — a powerful tool for awakening nationalist spirit and resisting colonial rule.

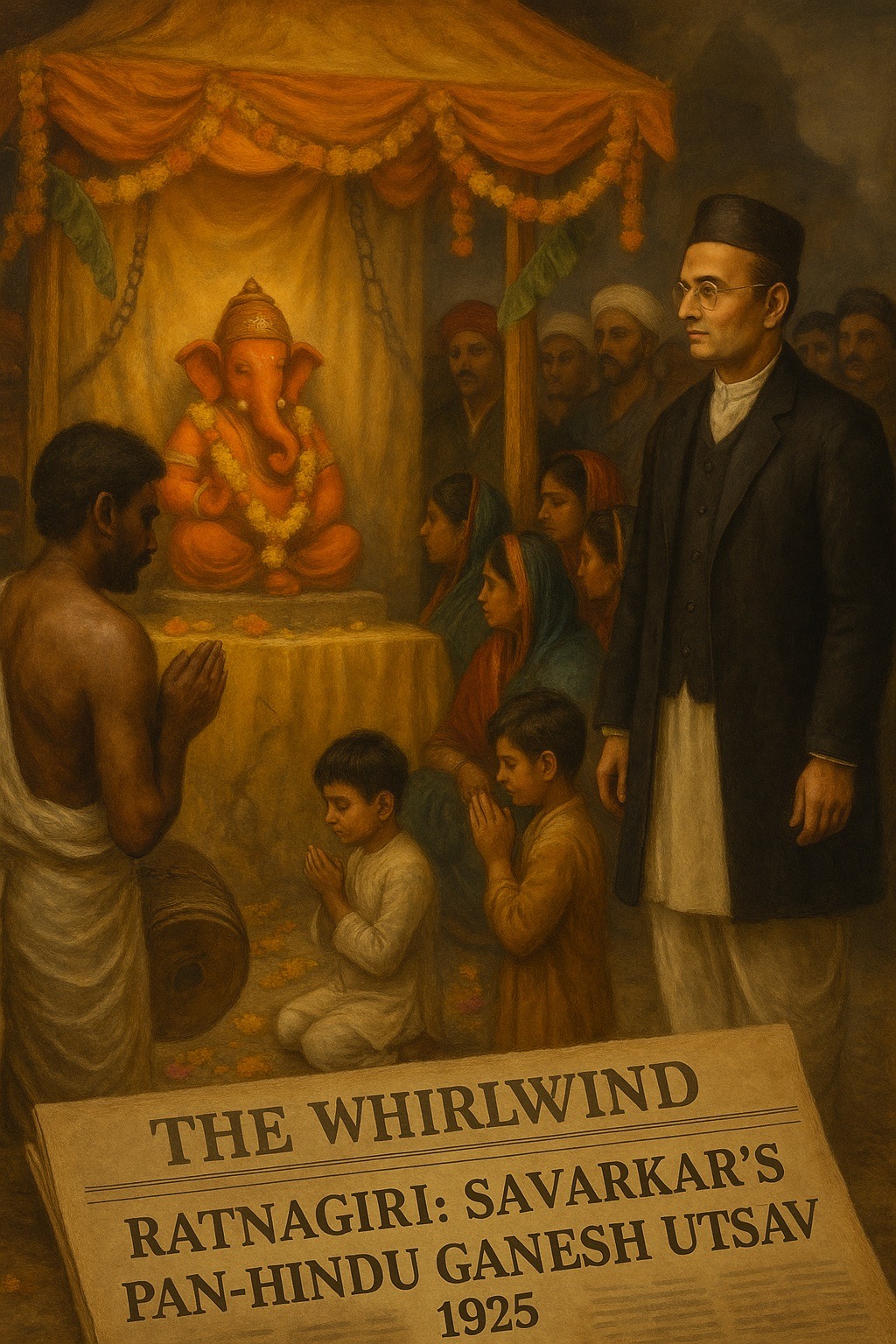

But three decades later, in 1925, another revolutionary, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (Veer Savarkar), gave the festival a new direction in Ratnagiri. For him, Ganesh Utsav was not only about devotion, but also about social reform and Hindu unity.

Breaking Orthodoxy

As biographer Dhananjay Keer writes, “to pull down the steel walls of orthodoxy, Savarkar started Pan-Hindu Ganesh Festivals in 1925. He transformed the Ganesh festival (Ganeshotsava) started by Tilak into a Pan-Hindu festival. An untouchable was not allowed for ages within the precincts of the Hindu sanctuary.” (Keer, Veer Savarkar, 1966, p. 181).

The immediate context was revealing: during the Ganesh festival, lower castes had been barred from entering the Vitthal Temple in Ratnagiri. Savarkar responded decisively by organizing a separate Ganapati festival that included people of all castes.

A Radical Gesture

What made Savarkar’s festival so striking was its symbolism of inclusion:

- The idol installation was performed not by a Brahmin priest but by a lower-caste devotee.

- The Gayatri Mantra recitation prize was awarded to lower-caste participants, breaking centuries of exclusion.

- Beyond rituals, the festival hosted lectures, public discussions, and articles highlighting the injustice of untouchability and its destructive impact on Hindu society.

For Savarkar, these were not small reforms but steps toward dismantling caste barriers. He believed firmly that “you cannot do substantial national work without the removal of untouchability.”

From Festival to Sanghathan

By reimagining Ganesh Utsav as a Pan-Hindu celebration, Savarkar turned a religious festival into a vehicle of social transformation and Hindu Sanghathan (unity). Where Tilak had emphasized political mobilization against colonial rule, Savarkar added a crucial social dimension: breaking the chains of caste division to build true national strength.

Legacy of 1925

Today, Ganesh Chaturthi has become one of the most vibrant festivals across India. Yet in Ratnagiri in 1925, it carried a deeper meaning — a call to rethink faith in the service of unity. Savarkar’s festival was not about abandoning tradition, but about reshaping it to serve the cause of equality and nationhood.

✍️ Final Thought: Savarkar’s Pan-Hindu Ganesh Utsav reminds us that festivals can be more than devotion — they can be platforms for social reform, cultural strength, and national awakening.

Sources:

KEER, Dhananjay. 1988. Veer Savarkar. Third Edition. (Second Edition: 1966). Popular Prakashan: Bombay (Mumbai).

GODBOLE, Vasudev Shankar. 2004. Rationalism of Veer Savarkar. Itihas Patrika Prashan: Thane/Mumbai.

Sampath, Vikram. (1921). Savarkar. (Part 2). A Contested Legacy. 1924-1966. Penguin Group: New Delhi.