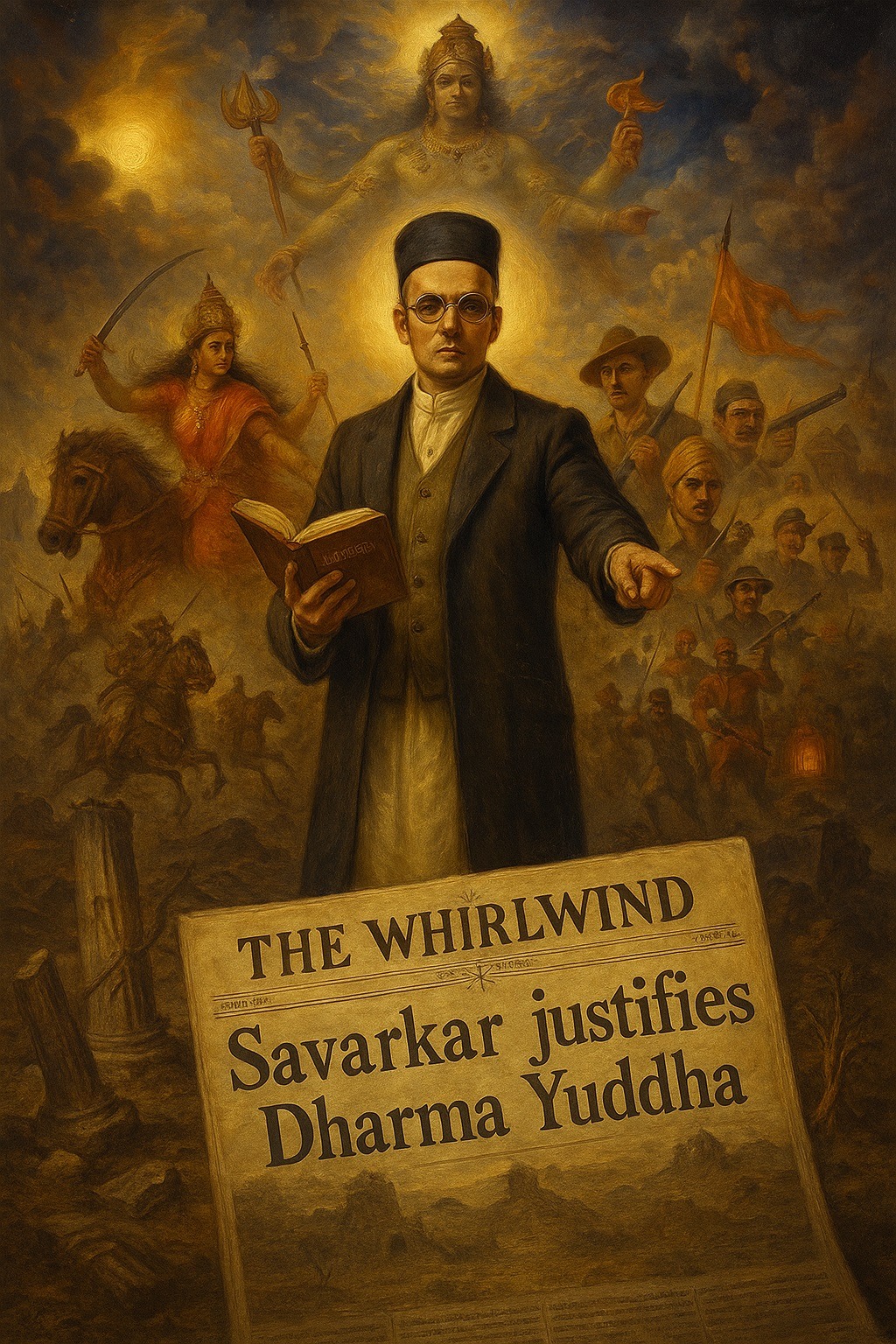

Political Dimension of Hindutva, Part 11

The idea of a “holy war,” known as Dharma Yuddha, against the enemies of Hindutva – particularly non-Hindu occupiers of the land – was a fundamental principle shaping Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar from his early youth. He derived this concept from the Bhagavad Gita, which speaks of the divine purpose of protecting the good and destroying evil. For Savarkar, the Dharma Yuddha was not merely a theoretical concept but an actionable framework that justified the use of force in specific socio-political contexts.

Justification of Violence in a Holy War

Savarkar viewed the “holy war” as a duty divinely ordained to protect the rights given by God. According to him, a revolutionary liberation movement is only “holy” if its underlying principle is strong and beneficial. He believed that both individuals and nations are judged by the character of their motives. Savarkar drew a clear distinction between wars of conquest, such as those waged by Alexander the Great, and national struggles for freedom, like the Italian liberation movements under Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi. He argued that only the latter could be considered a Dharma Yuddha, as they were fought for the protection of one’s people, land, and culture.

The Operationalization of Dharma Yuddha

Savarkar applied this concept to India’s struggle against British colonial rule, framing it as a continuation of the timeless battle between good and evil. He linked it historically to Hindu resistance against Islamic rulers, particularly during the era of the Maratha king Shivaji, and also drew parallels with Italy’s fight for national unification. The notion of a “holy war” first inspired him at the age of ten, leading him to swear an oath before the shrine of his family deity, Goddess Durga, to fight for India’s independence.

Durga, revered for slaying the buffalo demon Mahishasura, symbolized the triumph of good over evil, reinforcing Savarkar’s justification for militant resistance. However, his vision extended beyond a defensive struggle. He conceptualized a Digvijaya – a military and cultural conquest to defend and expand Hindu traditions against external influences.

The Role of Militancy and National Strength

Savarkar believed that history demonstrated the necessity of martial spirit for national survival. According to him, Hindus had historically fallen victim to invasions due to their inability to form a united military force, whereas Muslim conquerors succeeded due to their social cohesion and passionate bravery, fuelled by religious conviction. He argued that a society raised in a militant religious spirit, willing to eradicate opposing faiths through force or deception, had a greater ability to dominate than one that embraced pacifism.

This belief led him to a strong rejection of Buddhism, particularly its principle of absolute non-violence (ahimsa). He saw Buddhism’s state-sponsored propagation under Emperor Ashoka as a cause of Hinduism’s decline, weakening India’s defensive capabilities and making the nation vulnerable to foreign aggression.

Religious Unity and the Right to Exist

Savarkar emphasized that a nation’s right to exist depended on its ability to defend itself. He was convinced that it is not the number of aggressions a nation faces that determines its vitality, but whether it can ultimately repel these aggressions. Every nation’s history, he argued, consists of defining battles that shape its national identity. He saw India’s struggles against foreign rulers as fundamental to its nationhood.

The Maratha Resistance and Historical Legitimization

Savarkar admired the guerrilla warfare tactics employed by the Marathas against Muslim rulers, legitimizing them through references to ancient Sanskrit texts. He highlighted the term Vrakyuddha, an old Sanskrit designation for guerrilla warfare, reinforcing the historical continuity of this strategy. Despite using religious terminology, he maintained that military victory was superior to religious victory, asserting that an armed victory without religious foundation could be dangerously unrestrained, whereas a religious victory without military strength was ineffective.

Final Thoughts – Savarkar’s Dharma Yuddha and the Ethics of Struggle

Savarkar’s Dharma Yuddha was more than just a theoretical construct—it was a call to arms for Hindus to reclaim their sovereignty through militant struggle. By framing violence as a divine necessity for national survival, he sought to inspire a unified and aggressive Hindu identity. His ideology continues to be a subject of intense debate, reflecting broader tensions between nationalism, religion, and the ethics of warfare in modern India.

💭 What do you think? How do you interpret Savarkar’s idea of Dharma Yuddha — as a moral duty, a political strategy, or a theological justification for resistance? Can the concept of a “holy war” be ethically reconciled with modern ideas of non-violence and human rights? Do you think Savarkar’s distinction between wars of conquest and wars of liberation holds relevance in today’s global conflicts? In linking India’s struggle for independence with the Bhagavad Gita’s doctrine of righteous action, was Savarkar spiritualizing politics — or politicizing spirituality? How do you view Savarkar’s critique of Buddhism and Ashokan pacifism — as a historical observation or a political reinterpretation? To what extent can a nation’s survival depend on cultivating a “martial spirit,” as Savarkar believed? Does Savarkar’s notion of Digvijaya (military and cultural expansion) contradict his call for a defensive struggle, or does it complement it? What lessons, if any, can be drawn from Savarkar’s Maratha model of resistance for understanding contemporary forms of national defense and unity? Can moral justification and militant action coexist within the same framework — or do they inherently contradict one another?

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1970. The Indian war of Independence 1857. Rajadhani Granthagar: New Delhi.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1971. Six glorious (golden) epochs of Indian history. Savarkar Sadan: Bombay. 1971.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2009. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar und sein Hindutva-Konzept. Die Konstruktion einer kollektiven Identität in Indien [“Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his concept of Hindutva: The construction of a collective identity in India.”]. Online Dissertation: Heidelberg University: Heidelberg.

Leave a Reply