Political Dimension of Hindutva, Part 1

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar dedicated much of his intellectual energy to defining what it truly means to be “political.” One of the most profound areas where he applied this understanding was in his classification of political prisoners. But what exactly did Savarkar mean by “political,” and how did he differentiate political actions from other forms of resistance? Let’s dive into his perspective.

Action as the Core of the Political

For Savarkar, the essence of political identity did not lie in personal interests or individual ambitions but in action. More specifically, he believed that an action could only be classified as political if it was motivated by purely political reasons, irrespective of whether it was carried out individually or collectively.

This perspective led him to argue that the question of guilt was irrelevant when determining who qualified as a political prisoner. It was not the legality or morality of an act that made it political but rather the broader goal it aimed to achieve. A crime committed for personal gain remained a crime. However, if the same act was driven by the goal of national liberation or a greater public cause, it took on a political character (Savarkar 1950:401).

Political vs. Private Actions

Savarkar made a crucial distinction between political and private actions. According to him, no action was inherently political – it was the motive behind it that determined its nature.

For example, a rebellion fought solely for personal survival, such as securing food and livelihood, was not political. Similarly, an act of violence committed purely for personal gain did not qualify as political. However, if the same act was carried out to challenge foreign rule or establish a broader societal benefit, it transcended the realm of crime and entered the domain of political struggle (Savarkar 1924:610).

Even when the methods used were morally or legally questionable, the national significance of an act could elevate it beyond mere criminality. This distinction was crucial for Savarkar’s framework of political activism and resistance.

Who Are Political Prisoners?

Applying this framework, Savarkar classified prisoners in the Andaman cellular jail into two groups:

- Bomb Throwers – Individuals who engaged in acts of terror through treason and incitement. These individuals, in his view, fought in a reckless manner, causing chaos without a structured political objective.

- Political Prisoners – Revolutionaries who actively fought against colonial rule and were convicted for their activities. While they also resorted to violence, their fight was guided by a broader political vision.

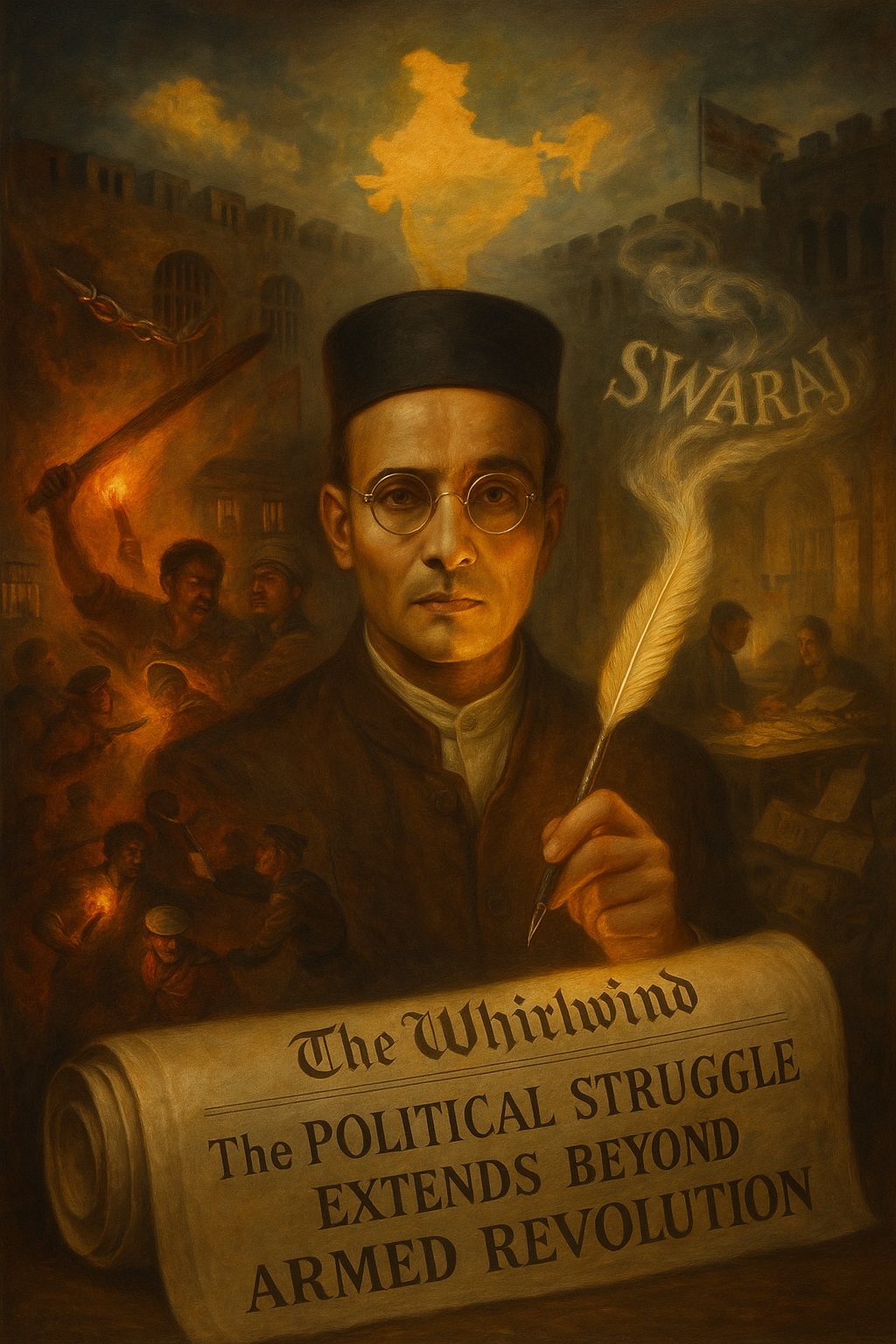

The key difference between these groups, according to Savarkar, was that political prisoners did not rely solely on physical violence. While they may have used weapons like bombs and pistols, they also wielded the power of the written word. This, in Savarkar’s eyes, was the most significant distinction: political prisoners used language as a weapon to challenge colonial rule and advocate for Swaraj (self-rule) (Savarkar 1950:109).

The Power of Words in Political Struggle

Savarkar’s emphasis on the use of language highlights his belief that the fight for independence was not just about physical confrontation but also about shaping public opinion and fostering intellectual resistance. He recognized that true political struggle extended beyond armed rebellion – it required articulation, persuasion, and the ability to inspire a movement.

In this way, his definition of the political remains relevant today. In an era where political struggles take place not only on battlefields but also in the media, academia, and digital spaces, Savarkar’s insights remind us that words and ideas can be just as powerful as physical actions in shaping the future of a nation.

Final Thoughts

Savarkar’s perspective on the political and his classification of political prisoners provide a nuanced understanding of resistance and activism. His emphasis on motive over mere action challenges us to look beyond the surface and examine the deeper intentions behind political movements.

Whether through direct action or intellectual discourse, Savarkar’s philosophy underscores the idea that politics is not just about fighting oppression—it’s about envisioning and articulating a new future. His legacy continues to inspire those who seek to challenge injustice and strive for national self-determination.

Sources:

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1950. The story of my transportation for life. Sadbhakti Publications: Bombay.

Leave a Reply