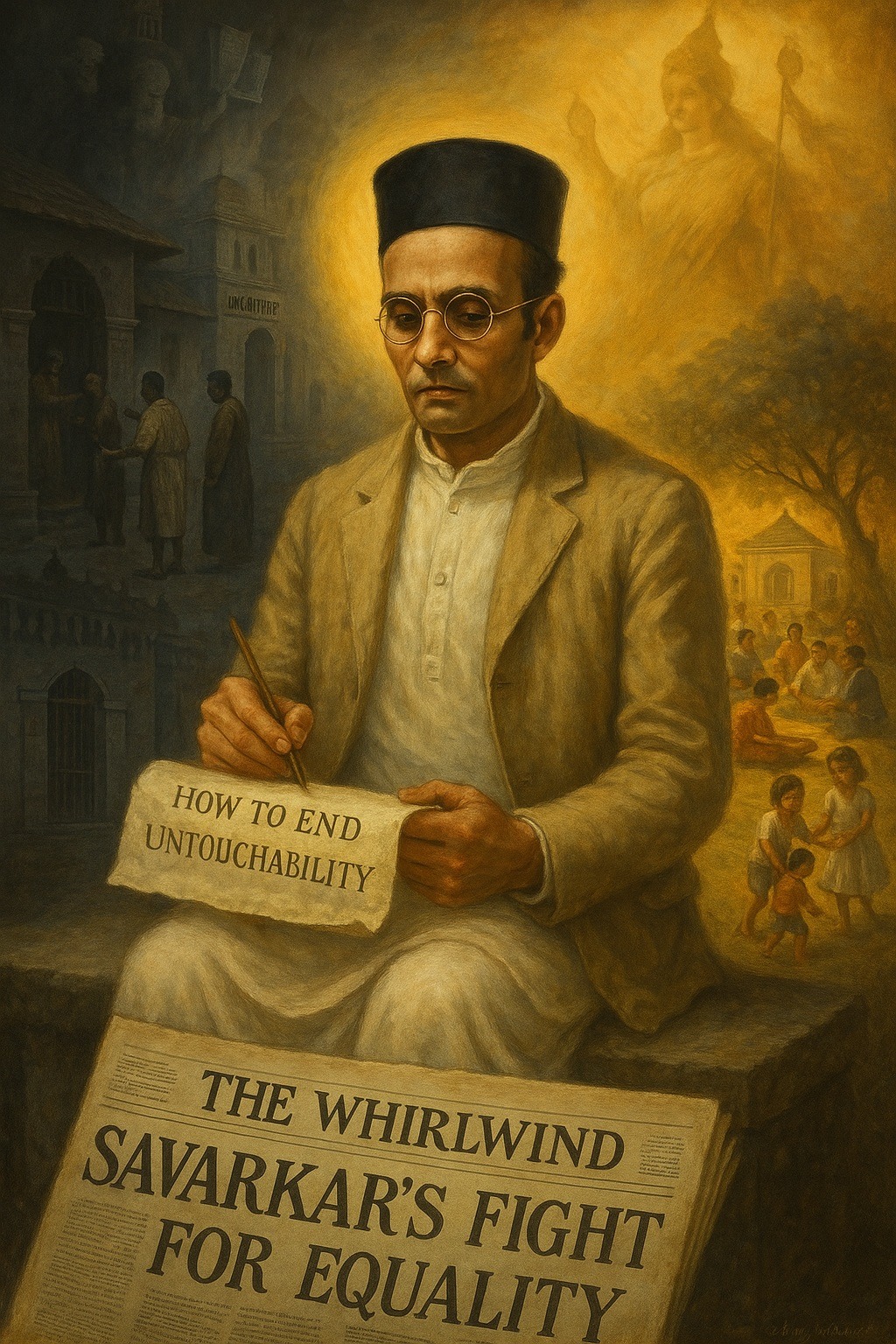

Savarkar’s Struggle Against Untouchability, Part I

Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar is often celebrated as one of India’s most fearless revolutionaries and intellectual architects of national liberation. Yet, beyond his political vision and militant struggle for independence, there lies another profound dimension of his legacy – his fight against untouchability.

During his years of confinement in Ratnagiri, Savarkar turned his attention from political resistance to social regeneration. He recognised that freedom from the British colonial rule would remain incomplete as long as millions of Indians were enslaved by the tyranny of caste. His struggle against untouchability became a central pillar of his reformist mission – a movement not merely of words, but of active, lived transformation.

In September 1927, Savarkar articulated his views on the subject in a powerful essay titled “A Warning to Our Untouchable Brothers,” published in the journal Shraddhanand. There, he wrote with unflinching moral conviction:

The current tradition of untouchability among Hindus is unjust and suicidal. No one needs to be informed about how sincerely I am working to eradicate it, least of all the readers of Shraddhanand. It is a heinous crime against 70 million people to treat them worse than animals. It is contemptible not only from the perspective of humanity but also for the sanctity of our inner soul.

Savarkar’s words cut through layers of complacency and hypocrisy, confronting both religious orthodoxy and social inertia. To him, untouchability was not merely a social evil – it was a moral catastrophe that corroded the very soul of the Hindu community.

The Social Realities of Untouchability

Untouchability, as Savarkar observed, was more than an abstract moral problem; it was a lived reality that dictated every aspect of life for millions. Its manifestations varied across India, but the essence was universal: humiliation, exclusion, and denial of human dignity.

In certain princely states like Travancore, the cruelty of caste discrimination reached extreme forms. Untouchables were denied even the most basic rights — their very existence was commodified. They were treated as property, often bought, lent, or exploited as bonded laborers.

Orthodox interpretations of Hindu scriptures helped sustain this system of oppression. Many caste Hindus sincerely believed they were divinely obligated to preserve these hierarchies. The notion of “pollution” — that an untouchable’s presence could defile sacred spaces – became a cornerstone of social exclusion. This belief governed every sphere of life:

- Religious Restrictions: Untouchables were barred from entering temples or joining processions.

- Access to Public Resources: They could not draw water from common wells or ponds.

- Social Isolation: They were excluded from public ceremonies, including weddings and festivals.

- Residential Segregation: They were forced to live outside villages, often in squalid and unsafe conditions.

Even during British rule, when legal reforms promised equality, change remained superficial. Legislative measures granting access to education or employment often failed to penetrate the caste-ridden mindset of Indian society. For instance, in Madras, untouchables were forbidden from entering courtrooms until as late as 1924.

Savarkar understood that no government decree could overturn centuries of inherited prejudice. The solution, he argued, lay in social awakening — in cultivating moral courage and collective will.

Savarkar’s Response: Reform as Revolution

Savarkar was not content with rhetoric. In Ratnagiri, he transformed his philosophy into tangible action. He organised campaigns, public dining events, and temple entry movements – encouraging upper-caste Hindus and so-called untouchables to share food, water, and worship.

He founded organisations dedicated to promoting social equality and personally participated in community meals, temple openings, and inter-caste interactions. For him, reform was not separate from nationalism — it was its very essence. A nation divided by caste, he declared, could never stand united against external enemies.

Savarkar’s social revolution in Ratnagiri was thus both ethical and strategic. It aimed to heal the inner fractures of Hindu society and forge a collective moral strength that could sustain political freedom.

Final Thoughts: A Continuing Legacy

Savarkar’s campaign against untouchability was radical for its time — a call to moral introspection and social reconstruction. He challenged the religious, social, and cultural foundations of inequality at a time when few dared to question them.

Stay tuned for Part II, where we explore Savarkar’s practical initiatives in Ratnagiri and their enduring impact on the struggle for social equality in India. His words from 1927 still resonate today as a reminder that political liberty without social justice is hollow. As Savarkar believed, a truly free nation must first liberate its conscience.

💭 What do you think? How do you interpret Savarkar’s view that social reform was essential for national freedom? Do you think Savarkar’s approach to eradicating untouchability differed from other reformers of his time, such as Gandhi or Ambedkar? In what ways? Can a nation truly achieve political independence without addressing internal social inequalities? How relevant is Savarkar’s message against untouchability in contemporary India? Do Savarkar’s grassroots actions in Ratnagiri offer lessons for today’s social reform movements? How might Savarkar’s ideas on unity and equality be reinterpreted in a 21st-century context? How does today’s India differ from Savarkar’s vision of an equal and united Hindu community?

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

GODBOLE, Vasudev Shankar. 2004. Rationalism of Veer Savarkar. Itihas Patrika Prashan: Thane/Mumbai.

KELKAR, B. K. 1989. „Savarkar: A Thee-dimensional view“, in PHAKE, Sudhir/PURANDARE, B. M. and Bindumadhav JOSHI. (Eds.). 1989. Savarkar. Savarkar Darshan Pratishtnah (Trust): (Bombay) Mumbai, 42-60.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1971. Six glorious (golden) epochs of Indian history. Savarkar Sadan: Bombay. 1971.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1924. An Echo from Andamans. Vishvanath Vinayak Kelkar: Nagpur, in GROVER, Verinder. 1998. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar: A biography of his vision and ideas. Deep and Deep: Publications: New Delhi.

VARMA, Vishwanath Prasad. 1985. Modern Indian Political Thought. Volume II. 8. Ed. Lakshmi Narain Agarwal: Agra, 386-391.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2010. Savarkar’s Strategic Agnosticism. A compilation of his political and economic worldview, in Heidelberg Papers in South Asian Comparative Politics (HPSACP), No. 51, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2009. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar und sein Hindutva-Konzept. Die Konstruktion einer kollektiven Identität in Indien [“Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his concept of Hindutva: The construction of a collective identity in India.”]. Online Dissertation: Heidelberg University: Heidelberg.

Leave a Reply