Savarkar’s Philosophy & Worldview, Part 7; Savarkar’s Agnosticism (4/4)

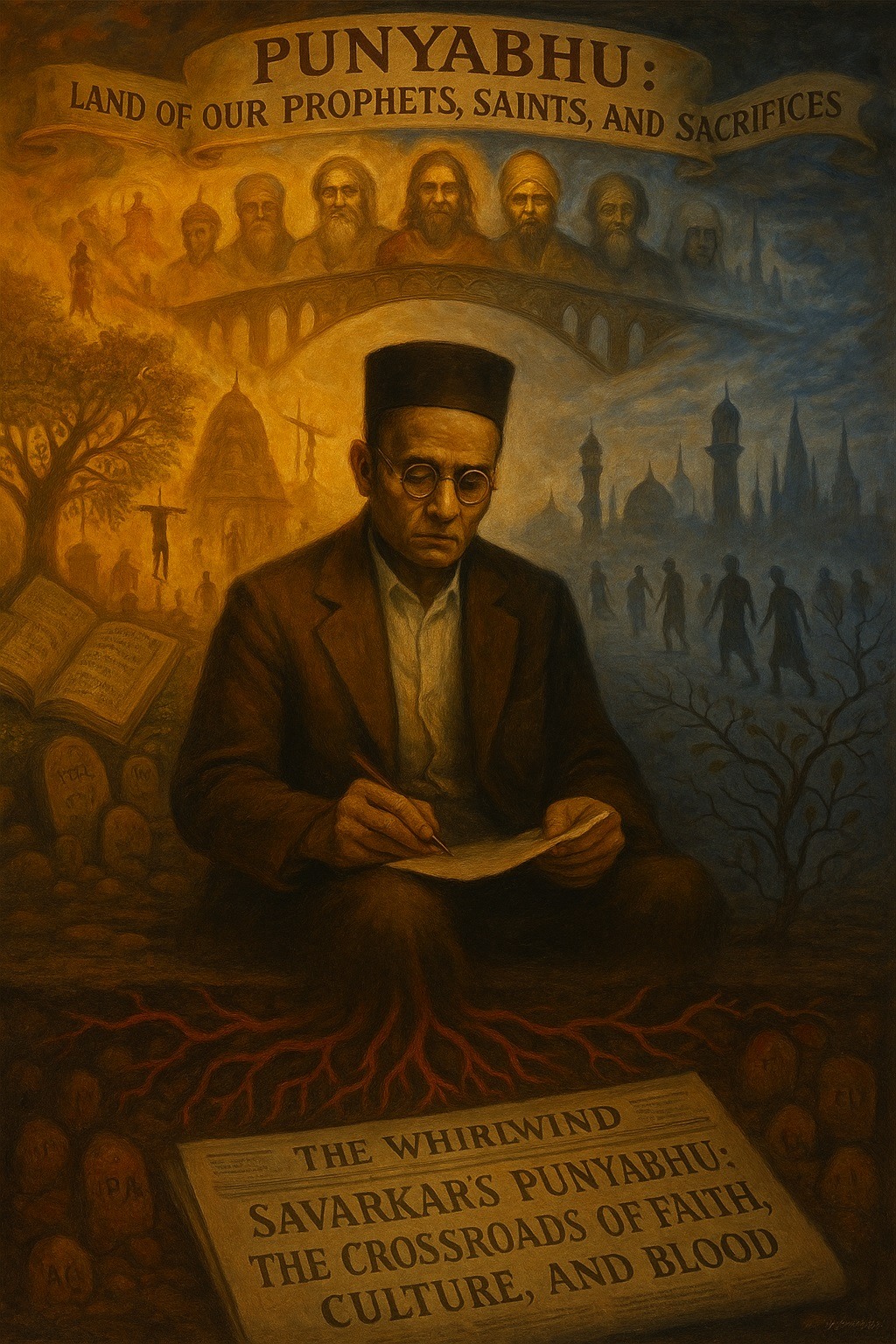

In the ongoing exploration of Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar’s agnosticism, one of the most intriguing and misunderstood concepts is his use of the term Punyabhu or Punyabhumi, often translated as “Holy Land.” This term has sparked significant debate, with both critics and supporters misinterpreting its meaning. For Savarkar, Punyabhu was not merely a religious construct but a deeply patriotic and cultural one, tied to his vision of Hindutva and the idea of a Hindu Rashtra. This essay delves into the nuances of Savarkar’s interpretation of Punyabhu, its implications, and the challenges it presents in understanding his worldview.

Punyabhu: Beyond Religious Merit

Traditionally, Punyabhu is understood as a land where one acquires religious merit through good deeds or spiritual practice. Savarkar redefined it in a way that emphasized patriotism and cultural identity over religious devotion. For him, Punyabhu was not just a land of pilgrimage or piety but a land of heroes, martyrs, and shared heritage. He described it as:

“The land of [his] prophets and seers, of saints and gurus, the land of piety and pilgrimages—where every stone can tell a story of martyrdom.”

This duality reveals Savarkar’s attempt to frame Punyabhu as a cultural and civilizational category rather than a strictly religious one. He tied it to Sanskriti – the collective expression of Hindu civilization—encompassing literature, art, history, social institutions, and festivals. While these elements often carry religious overtones, Savarkar insisted that they form part of a shared national heritage, not the property of a single faith.

The Challenge of Separating Religion from Culture

Despite Savarkar’s effort to secularize Punyabhu, the religious undertones are hard to escape. Terms like “rites,” “rituals,” “ceremonies,” and “sacraments” inevitably evoke religious imagery. Savarkar acknowledged this tension and clarified that his interpretation was personal—untied to any religious institution or dogma. For him, Punyabhu represented a common heritage at the national level, transcending sectarian boundaries.

Yet, this attempt to disentangle culture from religion created a continuum of interpretations—from contextual to literal—which profoundly shaped how Savarkar’s vision of a Hindu Rashtra would accommodate or exclude religious minorities.

Contextual vs. Literal Interpretations

- Contextual interpretation emphasizes patriotism and cultural assimilation. In this reading, non-Hindus could claim India as their Punyabhu if they embraced Sanskriti and demonstrated Desabhakti – undivided love for the homeland. Loyalty could be proven through participation in cultural life, without adopting all Hindu traditions.

- Literal interpretation insists that India must be the “holiest land” for all its inhabitants, with their most sacred sites located within its borders. This view excludes followers of non-indigenous religions like Islam and Christianity, whose sacred places – Mecca, Bethlehem, Rome – lie outside India. Savarkar’s controversial remark that “their love is divided” reflects this mistrust of non-Hindu loyalties.

A Middle Path: The “Extended Literal” Interpretation

Between these poles lies what may be called the extended literal interpretation, combining contextual and literal elements. It allows inclusion of non-Hindus if their important holy sites are in India, while still prioritizing patriotism and loyalty as criteria of belonging.

This approach provides a counterweight to the exclusivism of the literal view, offering non-Hindus a path to demonstrate Desabhakti and integrate into Hindu society. Yet, it still relies heavily on religious markers—underscoring the unresolved tension in Savarkar’s effort to secularize Punyabhu.

Strategic Agnosticism and Political Mobilization

Savarkar’s reliance on religious imagery in defining Punyabhu reveals a strategic dimension. Though he claimed his concepts of Hindutva and Punyabhu had little to do with religion or atheism, his pragmatic use of religious symbolism suggests what can be termed strategic agnosticism.

As Lederle observes, this strategy enabled the mobilization of diverse groups under a shared national identity, regardless of personal belief. Savarkar himself declared:

“Some of us are monists, some pantheists, some theists, and some are atheists. But whether monotheists or atheists, we are all Hindus and share a common blood.” (Savarkar 1999:56)

This inclusive yet tactical vision highlights his attempt to create unity beyond metaphysics while still drawing on religious language for political ends.

Final Reflections: The Legacy of Punyabhu

Savarkar’s concept of Punyabhu remains complex and contested, illustrating the difficulty of separating culture from religion in nationalist thought. His redefinition of the term as a cultural-patriotic construct was innovative but riddled with contradictions. The continuum of interpretations—from contextual to literal—underscores the challenge of applying the concept in a pluralistic society.

Ultimately, Savarkar’s use of Punyabhu demonstrates his pragmatic willingness to employ religious imagery for political mobilization, even as he distanced himself from dogma. This strategic agnosticism is emblematic of his vision of Hindutva and the Hindu Rashtra – one that continues to provoke both scholarly debate and political reflection.

💭 What do you think? How do you personally interpret Savarkar’s idea of Punyabhu—as a religious, cultural, or patriotic concept? Does it succeed in bridging the gap between religion and patriotism, or does it fall short in addressing the complexities of India’s diverse cultural landscape? Do you think it is possible to fully separate religion from culture in the way Savarkar attempted? Which interpretation of Punyabhu—contextual, literal, or extended literal—do you find most convincing, and why? Can Savarkar’s “strategic agnosticism” still be applied in today’s pluralistic societies? Does the tension between inclusion and exclusion in Savarkar’s thought make his vision of Hindutva more relevant or more problematic today? What role should historical memory (heroes, martyrs, saints) play in shaping a nation’s identity? Do you agree that religious symbolism can be a powerful political tool, even in secular or agnostic frameworks?

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

KLIMKEIT, Hans-Joachim. 1981. Der politische Hinduismus. Indische Denker zwischen religiöser Reform und politischen Erwachen. Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden.

ROTHERMUND, Dietmar. 2003. „Asien und die Globalisierung in historischer Perspektive“. Referat im Rahmen der Tagung: Asien in der Globalisierung Weingartener Asiengespräche 2003. Akademie der Diözese Rottenburg-Stuttgart, Weingarten/Oberschwaben, 31.1.-2.2.2003

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1999. Hindutva: Who is a Hindu. Seventh Edition. Swatantryaveer Savarkar Rashtriya Smarak: Mumbai.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1909. O’Martyrs. India House: London.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2010. Savarkar’s Strategic Agnosticism. A compilation of his political and economic worldview, in Heidelberg Papers in South Asian Comparative Politics (HPSACP), No. 51, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Wolf, Siegfried O. 2009. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar und sein Hindutva-Konzept. Die Konstruktion einer kollektiven Identität in Indien [“Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his concept of Hindutva: The construction of a collective identity in India.”]. Online Dissertation: Heidelberg University: Heidelberg.

Leave a Reply