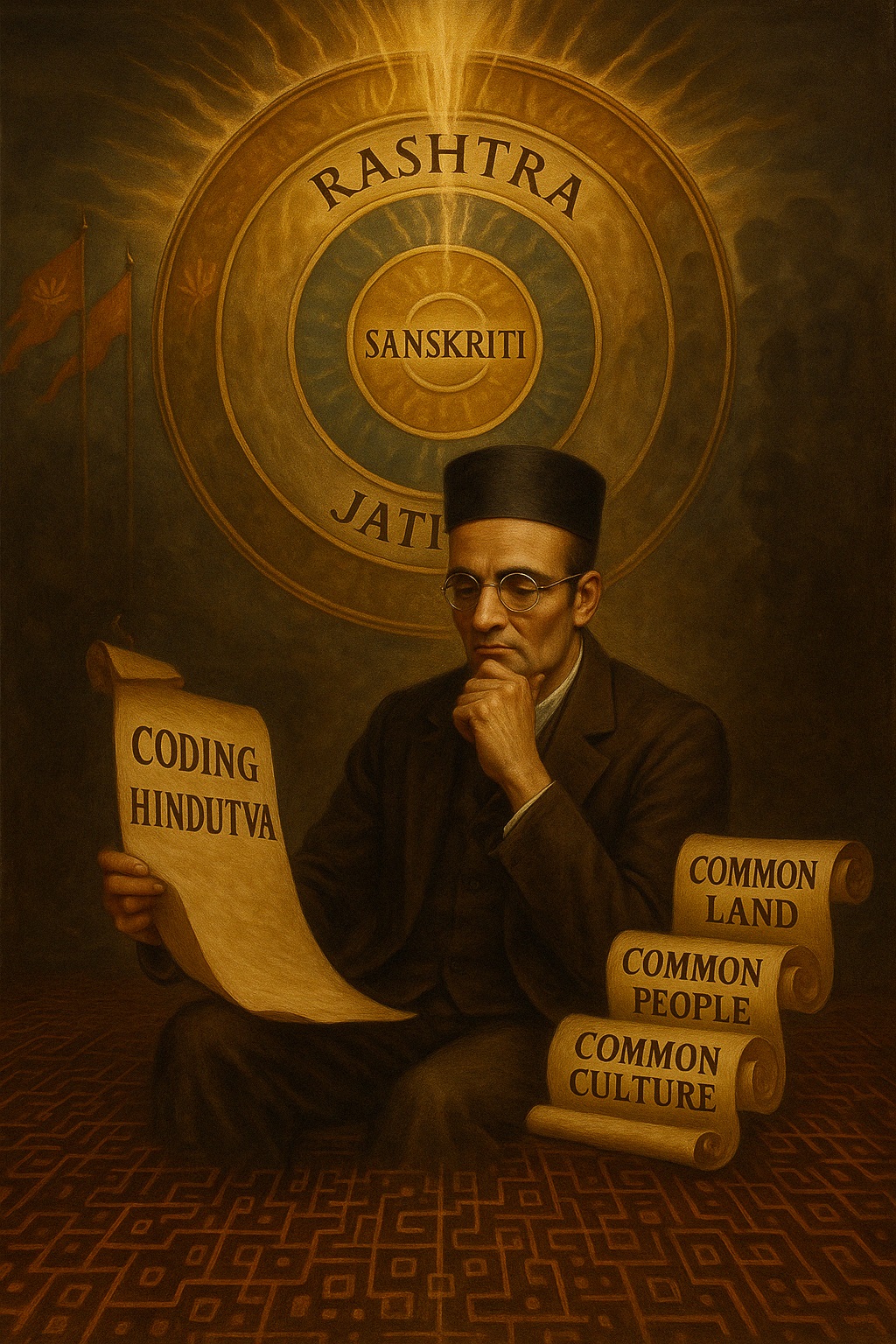

Savarkar’s Coding of Hindutva

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was the first to use the term Hindutva (literally “Hindu-ness”, the “quality of being Hindu”) in a comprehensive manner in his book Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?, published in 1923. Savarkar (1999:72) defined Hindus as all inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent who met three criteria:

- They regarded India as their fatherland (Pitribhu).

- They were of Hindu descent.

- They considered India a holy land (Punyabhu or Punyabhumi).

These three elements—Rashtra (common land), Jati (common people), and Sanskriti (common culture)—formed what he called the “essentials of Hindutva.” Unlike the term Hinduism, which Savarkar associated with religious disunity and social as well as political grievances, Hindutva was meant to define a cohesive national identity.

At the core of Hindutva is the belief that throughout Indian history, efforts were made to build a unified national entity across South Asia. However, Savarkar argued that these efforts failed due to the intrinsic heterogeneity of Hinduism, which he attributed to a misinterpreted form of tolerance. He believed this diversity led to a lack of universally binding social structures and, consequently, societal fragmentation. To counter this, Savarkar proposed the formation of a Hindu Sanghatan (a unified Hindu society) that would exclude heterogeneous elements.

According to Hindutva, such a society would only be realized through the establishment of a Hindu Rashtra—a Hindu nation founded on a monolithic Hindu culture (Kuruvachira, 2005:14). This process of nation-building (Hindu-Rashtravad) was envisioned as encompassing all aspects of societal life: social, economic, and political. The overarching goal of Hindutva—Hindu unity and the creation of a Hindu Rashtra—could only be achieved by addressing all three dimensions. In this way, Hindutva sought to fill what it perceived as a gap in national identity by constructing a collective identity that merged Hindu identity with Indian citizenship.

To fully understand the formulation of Hindutva, it is essential to analyze the structural design of its ideological framework. Savarkar employed both inclusionary and exclusionary strategies to define an ideal-typical citizen. By examining these strategies, we can trace the systematic elements of identity construction in his writings.

Savarkar’s conceptualization of Hindutva aligns with the sociological perspective that collective identities are socially constructed. This blog applies the framework of collective identity proposed by German sociologist Bernhard Giesen, who introduced the concept of “codes” as interpretive frames of social reality. According to Giesen (1999a), these codes are “purely symbolic structures, in no way bound to a location in space or temporal limits.” Collective identity is socially constructed through these codes, which serve as markers of meaning, helping both individuals and groups navigate the world. Examples of such codes include symbols, language, and myths.

To grasp the inner logic of identity construction within Hindutva, it is crucial to examine the codes Savarkar employed. Identifying the coherence between these codes reveals the mechanisms used to operationalize the idea of a homogenous Hindu society. Savarkar’s primary objective was not only to counteract the internal divisions among Hindus but also to justify the necessity of a Hindu Rashtra. In this sense, Hindutva serves as both an ideological justification for constructing India as a Hindu nation and a manifesto for its citizenship (Kuruvachira, 2005).

Crafting Hindutva: Codes of Construction

Without a collective identity—understood as a kind of social map—no cohesive community can exist, and without this foundation, stable nation-state structures cannot emerge. Humans structure their world through distinctions, and one of the primary distinctions in identity formation is the division between insiders and outsiders. The bond to a regional or national collective—whether real or imagined—is often constructed through the exclusion of those perceived as the other (Schmidtke, 1995:26). This distinction serves as the basis for social inclusion and exclusion, shaping collective identity. Giesen (1999b) refers to these bundles of distinctions as codes.

As mentioned earlier, Savarkar’s Hindutva is structured around three primary dimensions, each represented by a Metacode:

- Rashtra (Common Land)

- Jati (Common People)

- Sanskriti (Common Culture/Civilization)

These Metacodes are further constructed through specific codes, which are composed of code elements or subcodes. It is important to note that these elements are not rigid, isolated categories but exist within a dynamic framework of identity formation.

This blog series aims to systematically identify and analyze Savarkar’s approach to constructing Hindutva’s identity framework. By reconstructing his methodological approach, we will trace the consequences of his ideological framework and its impact on the meaning-making process of Hindutva.

Sources:

GIESEN, Bernhard. 1999b. Kollektive Identität. Die Intellektuellen und die Nation. Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main.

GIESEN, Bernhard. 1999a. „Codes kollektiver Identität“, in GEPHART, Werner and Hans WALDENFELS. 1999. (Eds.). Religion und Identität im Horizont des Pluralismus. Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, pp. 13-43.

KURUVACHIRA, Jose. 2005. Roots of Hindutva: a critical study of Hindu fundamentalism and nationalism. Media House: New Delhi.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1999. Hindutva: Who is a Hindu. Seventh Edition. Swatantryaveer Savarkar Rashtriya Smarak: Mumbai.

SCHMIDTKE, Oliver. 1996. Politics of Identity. Ethnicity, Territories, and the Political Opportunity Structure in Modern Italian Society. Sinzheim: Pro Universitate Verlag.

Leave a Reply