Savarkar’s Coding of Hindutva; Metacode Rashtra, Part 1

The concept of Hindutva is deeply intertwined with geography, history, and a unique cultural identity. At its core, the idea of Rashtra – the first Metacode – serves as the constitutive element of the “common land.” This Metacode not only defines the territorial framework of Hindutva but also embeds within it a profound sense of devotion, duty, and sacredness. The latter is envisioned through a national service of the individual towards the state (Code: Service to the Nation or National Service). Furthermore, the Metacode Rashtra is build on Savarkar’s notions of the Codes Territory, Desabhakti, and Myth.

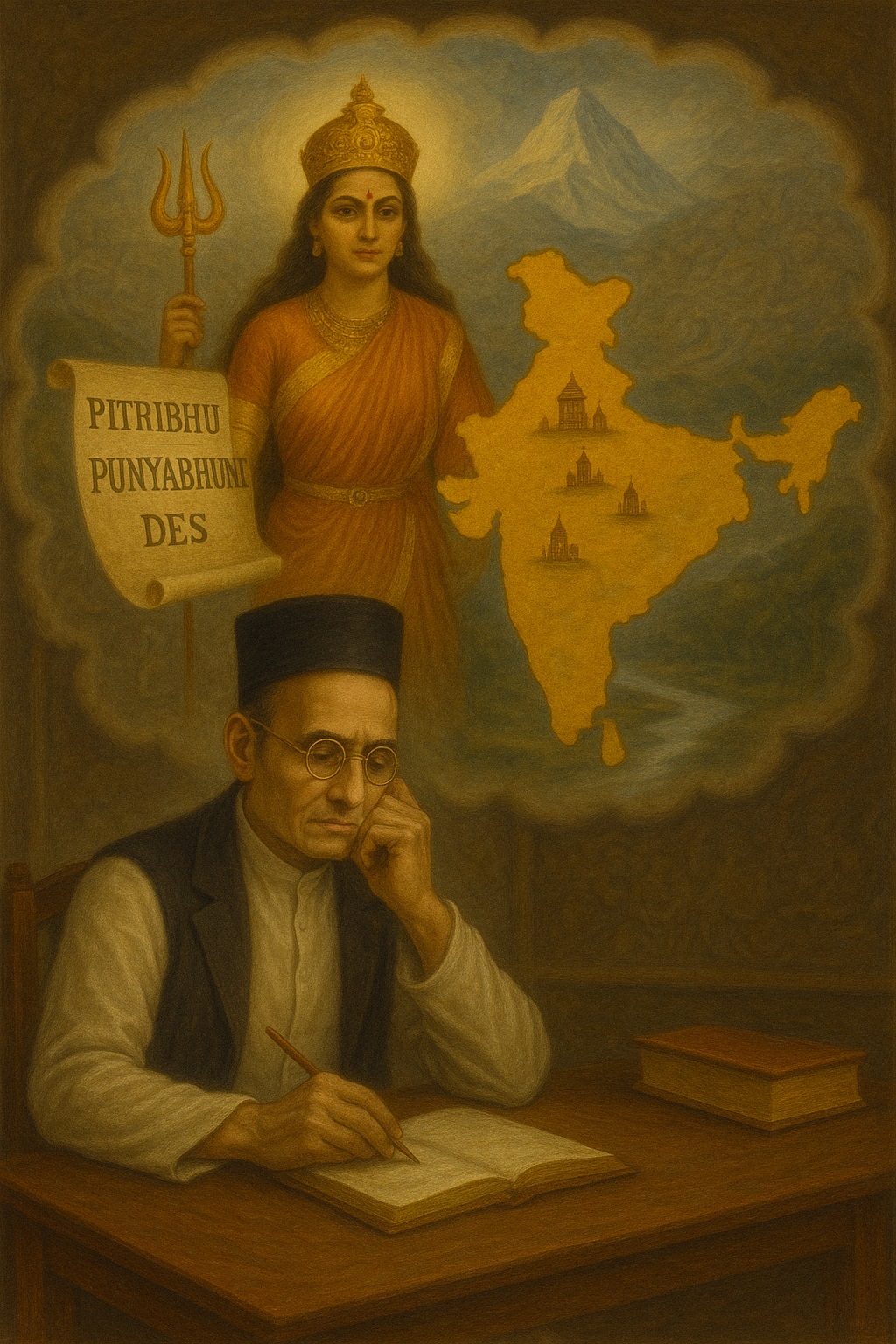

The Territorial Foundation (Code Territory): Pitribhu, Punyabhumi, and Des

The first dimension of Hindutva is structured around a geographical framework, which can be broken down into three key Codeelements:

- Pitribhu (Fatherland): The land historically claimed by Hindus as their own, forming the basis of their national identity.

- Punyabhumi (Sacred Land): A space elevated to a divine status, not merely a physical territory but a sanctified one, holding religious and spiritual significance.

- Des (Indivisibility of the Land): The inherent unity and indivisibility of this sacred geography, reinforcing a collective national consciousness.

This space unites fatherland and motherland and obliges service to the nation. The special significance of this space for Hindus arises, among other things, from the fact that it represents the land of their myths. It should also be noted that myths play a central role in the Hindutva concept. This concerns not only the justification of the sacredness of the Hindu territory, as explained in more detail in the post-series on the “Code Myth,” but also the underlying utopian-philosophical idea of seeing Hindus as the core of a universal world state.

Code Desabhakti

For Hindus, this land is more than just a physical space – it is a divine realm imbued with meaning, history, and responsibility. This sacred geography demands from its people an unwavering commitment, described by Savarkar as Desabhakti – a form of “divine love” towards the homeland. This obligation is not merely sentimental but manifests in patriotism and unwavering loyalty to the territorial unity of India.

The Mythic and Utopian Dimensions of Hindutva

The significance of this territorial foundation extends beyond geography; it is deeply embedded in mythology. Hindutva envisions Hindus as the core of a universal world state, with Bharat Bhumi (the land of the ancient hero Bharata) forming the epicenter of this vision. The Mahabharata, one of India’s foundational epics, narrates the deeds of Bharata, symbolizing the unity and grandeur of the land.

Savarkar articulates this idea succinctly by stating that anyone who considers this Bharat Bhumi from the Indus to the sea as their fatherland and holy land is a Hindu (Klimkeit 1981:248). This assertion highlights an intrinsic connection between territorial allegiance and religious-cultural identity.

Interestingly, Savarkar’s choice of terminology is deliberate. Instead of using Aryavarta, a term historically referring to the land of the Aryans north of the Vindhya Mountains (as used by Dayananda Saraswati), he opts for Bharat Bhumi. This distinction emphasizes a pan-Indian identity over an exclusionary, region-specific one, reinforcing a powerful, unified state identity.

Final Thoughts – The Nation as a Living Entity

Through this territorial conceptualization, Hindutva constructs a vision where the nation is not merely a landmass but a living entity, intertwined with history, mythology, and collective consciousness. It is a sacred space that demands devotion, preservation, and unity. By embedding these ideals in the first dimension of Hindutva, the philosophy extends beyond mere political ideology – it transforms into a civilizational ethos, deeply rooted in the cultural and spiritual psyche of its people.

What does “Rashtra” mean to you? Is patriotism a duty or a choice? Can myths shape a nation’s future? Do you think the concept of a ‘sacred geography’ is unique to Hindutva, or are there similar ideas in other ideologies or religions? Share your insights in the comments below!

Sources:

KLIMKEIT, Hans-Joachim. 1981. Der politische Hinduismus. Indische Denker zwischen religiöser Reform und politischen Erwachen. Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1999. Hindutva: Who is a Hindu. Seventh Edition. Swatantryaveer Savarkar Rashtriya Smarak: Mumbai.

Leave a Reply