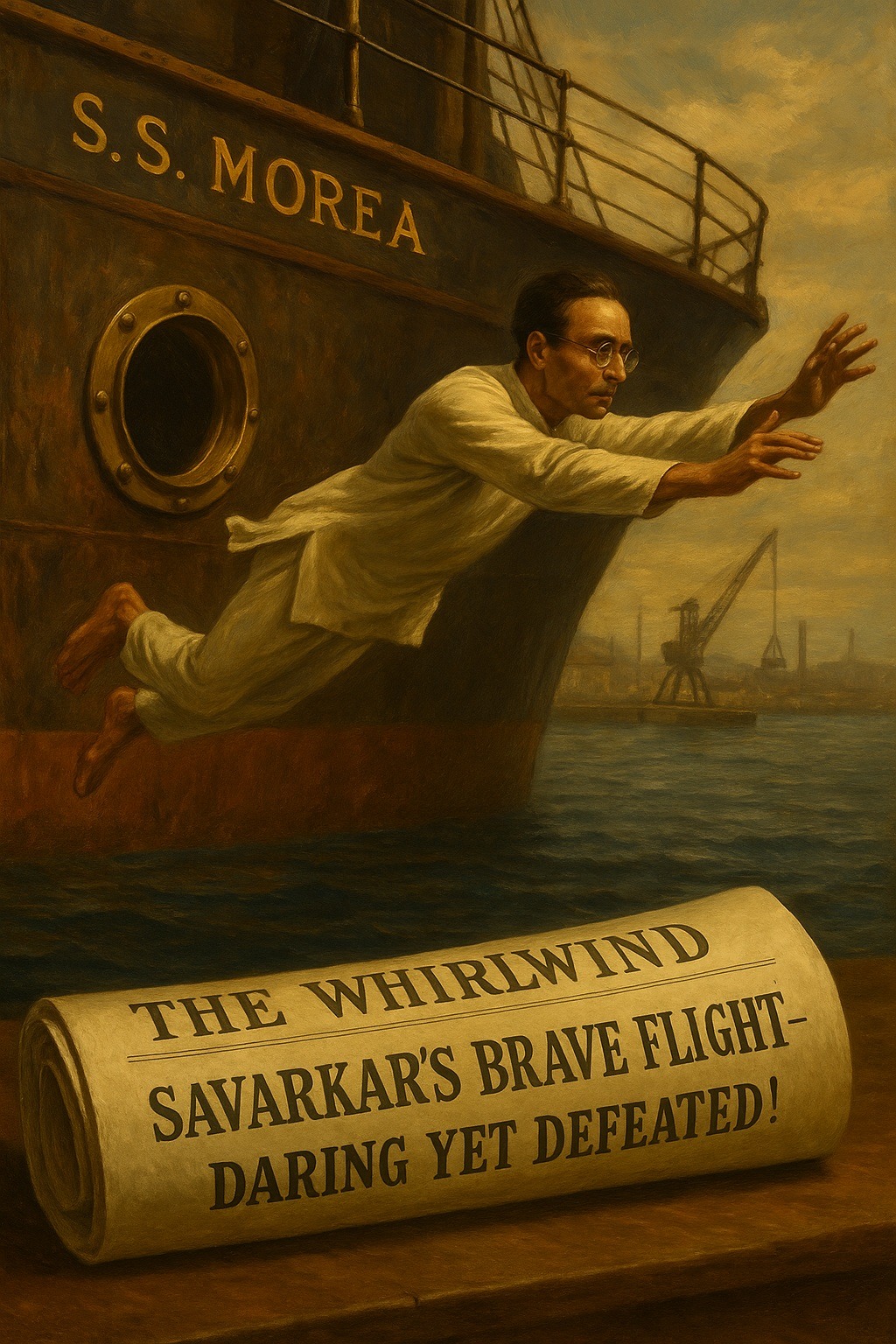

Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar’s escape attempt at the French port of Marseilles on July 8, 1910, remains one of the most daring and dramatic episodes in the history of Indian freedom fighters in Europe. Years later, in his final press interview, Savarkar himself described it as the most memorable event of his life. What unfolded in those frantic minutes between his leap into the harbor waters and his recapture on French soil would not only test his courage but also ignite a major international dispute

The Prelude

By mid-1910, Savarkar had become a prominent target of British intelligence for his role in radical nationalist activities in India and Europe in general and the Nasik Conspiracy Case in particular. Arrested in London, he was being sent back to India aboard the British India Steam Navigation Company steamer S.S. Morea to face trial – a trial that could end with his execution.

The Escape from the S.S. Morea

Savarkar was being held in a heavily guarded cabin. On July 7, the S.S. Morea lay at anchor in Marseilles harbor. On the morning of July 8, Savarkar seized his chance. During the entire journey from London to Marseilles, he had always been escorted by at least two of the four police officers assigned to guard him. Complaining of illness, he requested permission to use the lavatory. Seizing a moment of the guard’s distraction, he rushed down a corridor, squeezed himself through a small porthole, and leaped into the sea [there are differing historical accounts of this episode—see my notes below].

The guards on the ship raised the alarm and rushed across the deck, running down the gangway toward the quay to intercept him. Nevertheless, Savarkar swam and managed to reach the quay. His feet touched French soil—technically placing him outside British jurisdiction. He knew enough international law to realize that if the French police took him formally into custody, Britain would have to file for extradition, giving him the chance to claim political asylum. At least, that was Savarkar’s plan…

A Few Steps of Freedom

For a brief moment, Savarkar escaped his guards and staggered forward on French territory. But the escape had been anticipated. French police, primed by advance warnings, were already vigilant. Brigadier Pesquié of the maritime gendarmerie, along with other policemen, rushed at the exhausted fugitive. Savarkar managed only a short run of perhaps a hundred meters before he was seized.

Legacy of the Marseilles Escape

Though unsuccessful, the Marseilles escape cemented Savarkar’s reputation as a man of remarkable courage and strong will. The image of the shackled revolutionary squeezing through a porthole, diving into the sea, and sprinting toward freedom on foreign soil became a symbol of defiance against colonial rule.

Final Thoughts – A Few Notes

There is no doubt that Savarkar’s attempt to escape his British guards in the harbor of Marseille on 8 July 1910, was both extraordinarily difficult and an act of great bravery. Yet, as with all aspects of his life, thought, and action, a scholarly engagement requires us to remain attentive to the historical realities.

1. Conflicting accounts of the escape: Police records, as well as some historians (such as Vikram Sampath), state that Savarkar squeezed through the porthole and jumped directly into the sea. Other testimonies, including eyewitness notes, suggest that he may first have landed on a narrow maintenance ledge or a lower deck before diving into the water.

2. Water temperature: Since the escape took place in July, the water of the Marseilles harbour would not have been cold, contrary to what some accounts claim.

3. Distance to the quay: The distance between the ship and the quay was not “hundreds of feet” as occasionally described, but only about 10 to 12 feet. At the time of Savarkar’s escape, the Morea was docked for coaling and resupply, with a gangway in place — a factor that enabled the British guards to pursue him swiftly.

4. Steamer S.S. Morea – British, Not French: Contrary to some accounts, the S.S. Morea was a British ship, not a French one. It belonged to the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), a London-based British shipping line. Built in 1908 by Caird & Company in Greenock, Scotland, the vessel sailed (obviously) under the British flag.

💭 What do you think? What does Savarkar’s failed escape attempt tell us about courage in the face of impossible odds? Do you think the Marseilles incident would have changed history if French authorities had granted Savarkar asylum? Do you think Savarkar’s escape attempt strengthened his legend more than a successful escape might have? Does the exact physical detail of Savarkar’s leap matter for history, or is the symbolism more important? Should historians actively correct such embellishments, or leave them as part of the freedom struggle’s mythology? Do small factual inaccuracies (like “hundreds of feet”) undermine the credibility of revolutionary narratives, or are they simply part of the drama of storytelling? Is it more important for history to be factually precise, or emotionally inspiring?

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

KEER, Dhananjay. 1988. Veer Savarkar. Third Edition. (Second Edition: 1966). Popular Prakashan: Bombay (Mumbai).

SAMPATH, Vikram. 2019. Savarkar (Part 1). Echoes from a forgotten past. 1883-1924.Penguin Random House India: Gurgaon.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1965. Last Press Interview, conducted by Shridhar Telkar. [orginally published by the weekly ORGANISER and appeared in the Diwali number 1965]; reprinted in Savarkar. Commemoration Volume. Savarkar Darshan Pratishthan (Trust), edited by Sudhir Phadke, B.M. Purandare, Bindumadhav Joshi. February 26, 1989.

Leave a Reply