The dramatic London chapter of Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar’s life reached a decisive turning point in March 1910. On Sunday, 13 March 1910, Savarkar was arrested at Victoria Station while waiting for a train. For months, the British authorities had been keeping him under close surveillance, suspecting his involvement in revolutionary networks that had sprung from India House in Highgate. His name was increasingly linked with the radical activities of Indian nationalists abroad, and especially with the assassination of Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie by Madan Lal Dhingra the previous year.

From Victoria Station to Bow Street Custody

Following the arrest, Savarkar was taken into custody at Bow Street Police Station, a major metropolitan station known for handling political cases. There he was interrogated about his alleged role in distributing seditious literature and supplying arms to Indian revolutionaries. The police were especially interested in the trail of pistols that led back to the Nasik Conspiracy Case, in which his brother Ganesh Savarkar had already been convicted.

On 14 March 1910, Savarkar was formally charged and ordered to remain in custody while the case was being prepared. He was to face the Bow Street Police Court, one of the highest-profile venues of its kind in London.

The Bow Street Police Court Hearing

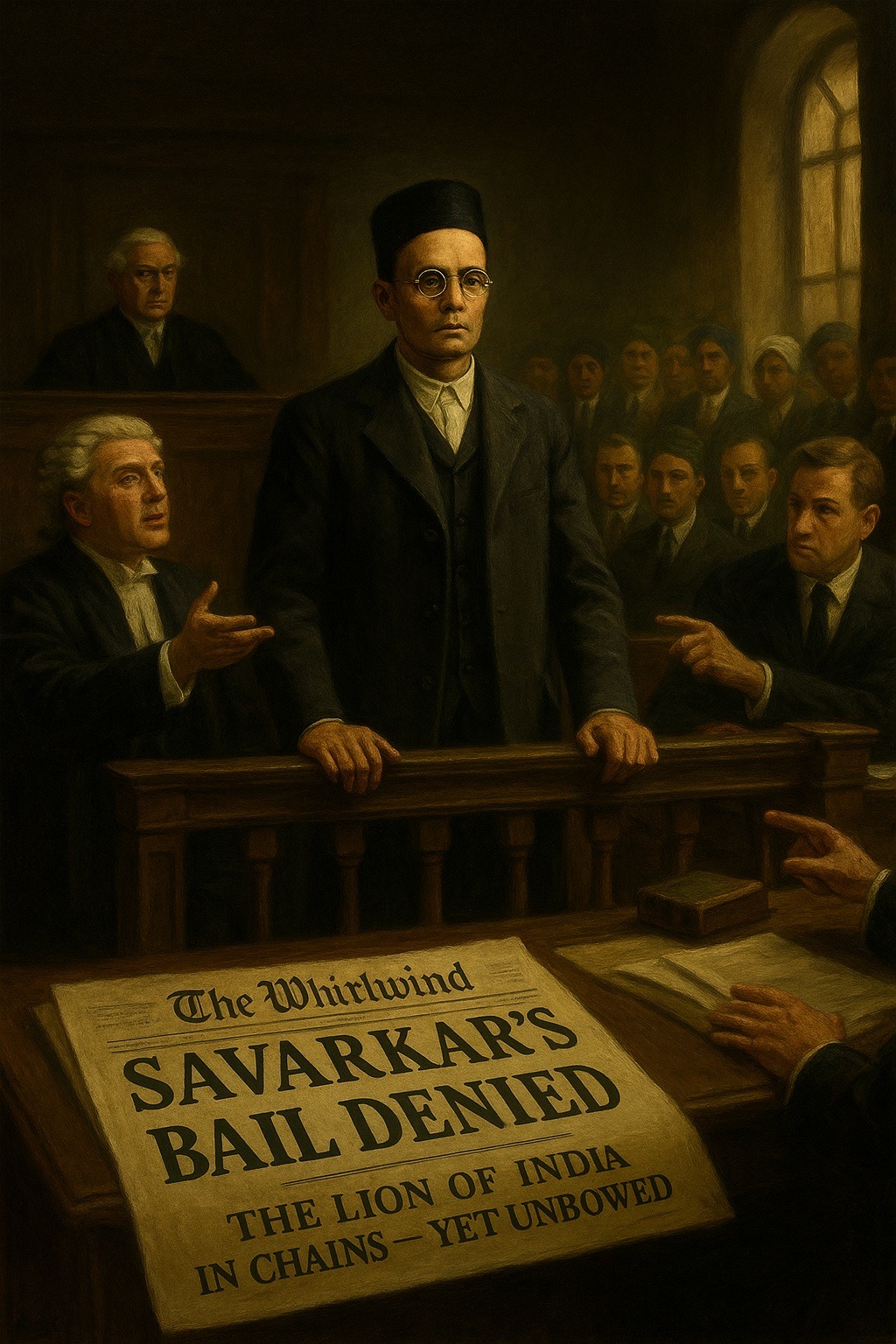

It was not until 20 April 1910 that Savarkar was brought before the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, Sir Albert de Rutzen. The hearing drew considerable attention. Contemporary reports note that the courtroom was crowded with spectators, many of them “well-dressed young Indians,” eager to show solidarity with their comrade. All of Savarkar’s close associates were present, including V.V.S. Aiyar, who worked closely with his defense team.

Savarkar’s counsel, Reginald Vaughan of Gray’s Inn, immediately applied for bail. Vaughan argued before the magistrate:

“There is very considerable doubt whether there is any authority to send this man back to India. This, however, is a question which your Worship will consider later. I ask in the meantime that this man shall be admitted to bail. The offence is of a political nature really; whether in law or not is another matter.”

The plea was a bold attempt to highlight the political rather than purely criminal nature of the charges. But the magistrate was unmoved. The Crown’s prosecution insisted that Savarkar was a dangerous revolutionary with possible foreign backing, and that he posed a serious risk of escape if released. They stressed his alleged role in smuggling pistols to India — the very weapons used in the assassination of A.M.T. Jackson, the Collector of Nasik, in December 1909.

When Vaughan pressed the matter — “No bail at all?” — Sir Albert de Rutzen replied curtly:

“Not until I know more about the case.”

The application was denied, and the case was remanded until 23 April 1910.

From Bow Street to Brixton Prison

After the hearing, Savarkar was transferred from Bow Street custody to Brixton Prison, where he was to remain under remand while the legal machinery of extradition was set in motion. The British Government in India had already requested his handover under the Anglo-French Extradition Treaty, preparing the way for his deportation back to Bombay.

Final Thoughts – The Larger Significance

Though technically a preliminary hearing, the Bow Street proceedings were crucial. By refusing bail, the court ensured that Savarkar remained under close watch until his eventual transfer to the French mail steamer S.S. Morea on 1 July 1910. This chain of custody directly set the stage for one of the most dramatic episodes of his life: the famous escape attempt at Marseilles, when Savarkar leapt into the sea in a bid for freedom.

The crowded courtroom at Bow Street in April 1910 thus became the scene of a turning point: a young revolutionary’s first open clash with British law on foreign soil, a denial of liberty that only intensified the struggle to come.

💭 What do you think? How do you think the arrest of Savarkar at Victoria Station in 1910 affected the Indian independence movement abroad? Did it symbolize a larger turning point? Why do you think the British court system chose to deny bail despite the defense’s political argument? How does this reflect the colonial attitudes towards Indian revolutionaries? The trial at Bow Street was a crucial event in Savarkar’s life. How do you think this moment resonated among other Indian nationalists at the time? Was Savarkar a symbol of resistance for others, and if so, how?

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

Bakshi, Surinder Mohan. (1999). Vinayak Damodar Savarkar: Life and Times. New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications.

Keer, Dhananjay. 1988. Veer Savarkar. Third Edition. (Second Edition: 1966). Popular Prakashan: Bombay (Mumbai).

Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra. (1975) Penal Settlement in Andamans. Calcutta: Department of Anthropology, University of Calcutta.

Nijjar, Bakhshish Singh. (1979). Origin and History of the Indian Revolutionary Movement. New Delhi: Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

Sampath, Vikram. 2019. Savarkar (Part 1). Echoes from a forgotten past. 1883-1924.Penguin Random House India: Gurgaon.

Shankar, Ravi (1924). “Savarkar in Europe from 1906 to 1910: A Reappraisal.” Contemporary Social Sciences, vol. 33, no. 2, June 30.

Leave a Reply