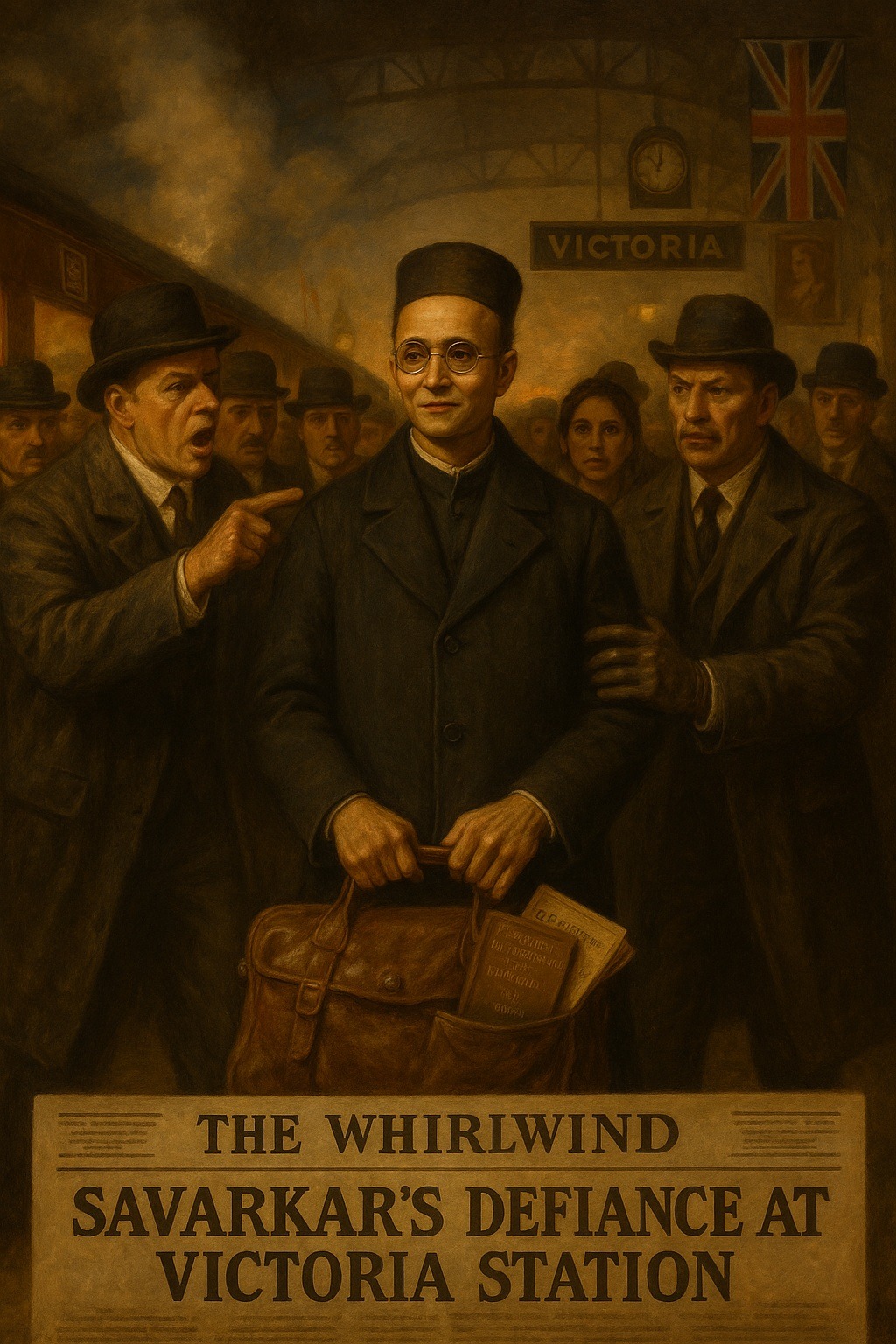

On Sunday, 13 March 1910, Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar’s revolutionary mission in Europe met a dramatic turning point. That evening, as he arrived by train from Newhaven (via Paris) at Victoria Station in London, he was arrested by officers of the Metropolitan Police under charges of sedition, conspiracy, and waging war against the British Crown. This arrest, which followed his unexpected departure from Paris, would set in motion a chain of events leading to his extradition to India and his legendary escape attempt at Marseille.

A Sudden Departure from Paris

Savarkar had been living in Paris, under the protection of Madame Bhikaji Cama, after British authorities began closing in on him in London. Though he had promised his associates, including Shyamji Krishnavarma, that he would meet them one final time before returning to London, Savarkar left Paris abruptly on the morning of Sunday, 13 March 1910. In a heartfelt letter, he expressed regret for being unable to bid them farewell and thanked them profusely for their generosity and unwavering support in the revolutionary cause.

Traveling by train from Paris to Calais, Savarkar crossed the English Channel and boarded a boat train from Newhaven Port bound for London. Alongside him was Miss Perinben Naoroji, the granddaughter of Dadabhai Naoroji, who was aiding the revolutionaries by assisting in the manufacturing of bombs. Remarkably, the police failed to detect her presence.

The Arrest at Victoria Station

At 7 p.m., as the boat train steamed into Victoria Station, Savarkar realized he was being shadowed. As soon as he stepped off the train, a swarm of detectives and police officers descended on him. Chief Inspector John McCarthy and Inspector E. John Parker of Scotland Yard—who had been pursuing the case for months—exclaimed triumphantly: “Here he is… he is here!”

Savarkar, calm and defiant, simply smiled and replied:

“Yes, it’s me… I am Savarkar.”

The Charges Against Savarkar

Savarkar was taken to a waiting room, where the arrest warrant from the Bombay High Court was read to him. The charges were sweeping, aimed at dismantling the revolutionary networks he had built both in India and Europe. Under the Fugitive Offenders Act of 1881, he was accused of:

- Waging war or abetting war against His Majesty the King-Emperor of India.

- Conspiring to overthrow British sovereignty in India.

- Procuring and distributing arms, including the Browning pistols smuggled to India.

- Aiding the assassination of A.M.T. Jackson, the Collector of Nasik (1909).

- Delivering seditious speeches in India (1906 onward) and London (1908–1909).

When informed of these charges, Savarkar responded with quiet defiance:

“Yes, sir! Doubtless the case would prove very interesting!”

Scotland Yard’s Search

Savarkar was transferred to the Bow Street Police Station. A search of his belongings revealed incriminating material, including:

- Two copies of The Indian War of Independence of 1857, his banned historical work.

- Seven copies of the pamphlet Oh! Ye Princes, which called for Indian rulers to unite against British rule.

- One copy of Mazzini, the writings of his Italian revolutionary idol.

- Several articles, journals, and newspaper cuttings.

This evidence painted Savarkar as a dangerous revolutionary, deeply connected to arms smuggling and underground networks. It was also known that one of the Browning pistols he helped procure was used by Anant Laxman Kanhere in Jackson’s assassination.

Savarkar’s ‘Ides of March – Was he Trapped?

Some accounts suggest that Savarkar’s return to London was a grave mistake—possibly orchestrated by a British agent named Margaret Lawrence, who allegedly lured him back with the promise of romantic interest (the so-called “honey-trap” rumor).

Although there is no solid evidence to support this claim, it remains a persistent tale in revolutionary lore. Historian Dhananjay Keer comments on this narrative, stating: “Scotland Yard sedulously spread a story that Savarkar had fallen a victim to a false letter they had manoeuvred in the name of a girl!”

A more reasonable explanation, however, is that Savarkar still retained some faith in the British judicial system and believed he could defend himself fairly. Moreover, his return was driven by political necessity—to coordinate nationalist activities and maintain his influence at India House—rather than by any supposed romantic entanglements. If personal motives played a role, it was because he could not tolerate the thought of his comrades and followers facing persecution in London while he remained in the relative safety of Paris. On this point, Keer quotes Savarkar rejecting the pleas of his friends to stay in France: “I cannot see the persecution of my colleagues and followers. As a leader, I must face the music.”

Whatever the reason, Savarkar’s decision to return to London ultimately sealed his fate, leading to his arrest and subsequent extradition proceedings.

The Legal Battle

Savarkar’s legal counsel, Reginald Vaughan of Gray’s Inn, fought to secure bail, exclaiming in frustration, “No bail at all?” when the magistrate, Sir Albert de Rutzen, refused any leniency. From this point, Savarkar’s journey toward extradition to India began, ultimately culminating in his legendary yet unsuccessful escape attempt at Marseille in July 1910.

💭 What do you think? Do you think Savarkar’s sudden decision to leave Paris was an act of courage or a strategic miscalculation? What strikes you most about the way Savarkar reacted to his arrest—his calm defiance or his willingness to face the charges? What role do you think evidence like pamphlets and revolutionary literature played in shaping the British perception of Savarkar as a threat? Do you see parallels between Savarkar’s strategy of propaganda, underground networks, and modern movements for political change today?

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

KEER, Dhananjay. 1988. Veer Savarkar. Third Edition. (Second Edition: 1966). Popular Prakashan: Bombay (Mumbai).

PHAKE, Sudhir/PURANDARE, B. M. and Bindumadhav JOSHI. (Eds.). 1989. Savarkar. Savarkar Darshan Pratishthan (Trust): Bombay (Mumbai).

PINCINCE, John. 2007. On the Verge of Hindutva: V.D. Savarkar, Revolutionary, Convict, Ideologue, c. 1905–1924. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of Hawai‘i (at Mānoa) in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History.

SAMPATH, Vikram. 2019. Savarkar (Part 1). Echoes from a forgotten past. 1883-1924. Penguin Random House India: Gurgaon.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1993. Inside the enemy camp. Veer Savarkar Prakashan: Mumbai.

Shankar, Ravi. 2024. “Savarkar in Europe from 1906 to 1910: A Reappraisal.” Contemporary Social Sciences 33 (2): 78–87. https://doi.org/10.62047/CSS.2024.06.30.78.

SRIVASTAVA, Harindra. 1983. Five stormy years: Savarkar in London (1906-1911) – A centenary salute to V.D. Savarkar. Allied: New Delhi.

Leave a Reply