When we think of the modern Ganesh Chaturthi festival (Ganeshotsava), one name inevitably comes to mind: Bal Gangadhar (Lokmanya) Tilak, who in the 1890s transformed it from a private household ritual into a public celebration of unity and resistance against colonial rule.

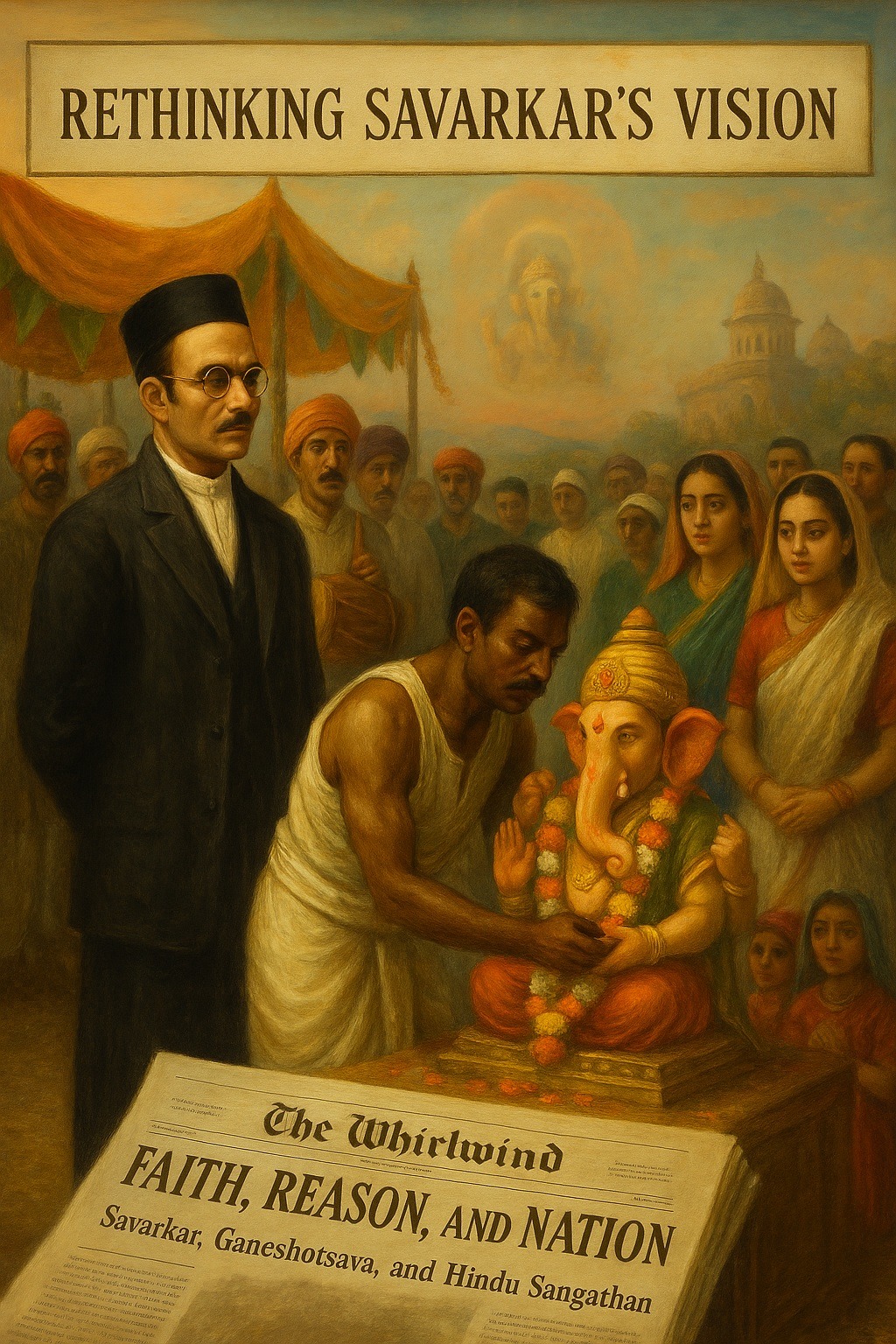

But what about Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar? Despite organizing a Pan-Hindu Ganesh Utsav in Ratnagiri in 1925, his name is rarely associated with the festival in public discourse. There are reasons for this. Savarkar was a “believing, strategic agnostic” — guided more by rationalism and political strategy than by deep spirituality. He was not hostile to religious belief, but he remained deeply skeptical of dogma and ritualistic superstition.

Yet, despite his distance from devotionalism, Savarkar clearly understood the political power of religion. He recognized that festivals like Ganesh Chaturthi could transcend ritual and become engines of solidarity, discipline, and collective consciousness.

Religion as Cultural Force, Not Blind Faith

Savarkar’s thought was marked by a striking duality. On the one hand, he denounced astrology, idol worship, and miracles, insisting that true progress required reason, science, and reform. On the other hand, he did not dismiss religion outright. For him, religion mattered less for its theological content than for its cultural force — its ability to unify and sustain the Hindu community.

It provided symbols, myths, and occasions that could mobilize millions. In this sense, Ganesh — the remover of obstacles (Vighnaharta) — became less a divine being than a metaphor for collective struggle and a symbol of national unity. Just as Tilak had used Ganesh Utsav to awaken nationalist sentiment, Savarkar saw in such festivals the seeds of Hindu Sanghathan: the organized unity of Hindus as a political and cultural force.

Hindutva and the Nationalization of Tradition

Savarkar’s concept of Hindutva was not about private faith but about a shared civilizational identity rooted in common land, culture, myths, and history. Festivals like Ganesh Chaturthi exemplified how Hindu tradition could be nationalized — transformed into a weapon of resistance against colonial domination and, ultimately, into a building block of a cohesive Hindu community (Hindu Sanghathan) working toward a future Hindu Rashtra.

In short, Savarkar’s approach to religion moved along two tracks: rejecting superstition while harnessing symbols and rituals for the higher purpose of political awakening. This duality earned him both admiration and sharp criticism from his contemporaries.

From Ritual to Sanghatan

For Savarkar, the purpose of any festival was not devotion alone but discipline, organization, and unity across caste lines. He argued that Hindus could never hope to resist colonial oppression or achieve freedom if they remained fragmented by ritual purity and caste exclusiveness. In this sense, Ganesh Utsav offered a model: a once-private ritual turned into a public forum of equality and nationhood.

A Lasting Tension

There is a permanent tension in Savarkar’s legacy: an agnostic who distrusted religious faith, yet a strategist who relied on religion’s symbolic power to forge Hindu unity. Ganesh Chaturthi stands at this very crossroads. While Savarkar himself did not elevate the festival in the way Tilak had, it embodies the kind of cultural resource he sought to transform into political strength.

Final Thoughts: The Nation as the New Sacred

Savarkar’s ultimate aim was clear: to redirect the devotional energies of the people away from superstition and toward the service of the nation. In his vision, the Rashtra (nation) itself became sacred — a higher ideal that absorbed and redefined the religious life of the people.

Thus, when we see Ganesh Utsav today — massive, vibrant, and infused with nationalist symbolism — we are also witnessing echoes of Savarkar’s vision: a vision in which the gods of tradition were recast as symbols of collective destiny, and religion itself was retooled as an instrument in the making of a strong and independent Hindu Rashtra.

💭 What do you think? Do you see Savarkar’s approach to religion — rejecting superstition but embracing cultural unity — as a strength or a contradiction? Does his critical stance toward superstition make him more relevant, or less relevant, in contemporary debates on religion and society? Can religious festivals truly transcend faith and become primarily political or cultural symbols, as Savarkar envisioned? 👉 Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources

KEER, Dhananjay. 1988. Veer Savarkar. Third Edition. (Second Edition: 1966). Popular Prakashan: Bombay (Mumbai).

GODBOLE, Vasudev Shankar. 2004. Rationalism of Veer Savarkar. Itihas Patrika Prashan: Thane/Mumbai.

Sampath, Vikram. (1921). Savarkar. (Part 2). A Contested Legacy. 1924-1966. Penguin Group: New Delhi.

Leave a Reply