In the late 19th century, India was a country simmering with tensions—political, religious, and cultural. The British colonial regime‘s policy of divide and rule had deepened communal divisions. Against this backdrop, a teenage Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar, growing up in the village of Bhagur near Nashik, encountered one of the first defining moments of his life: a symbolic act of resistance that has since become the subject of both reverence and critique.

A Climate of Polarization

The years 1893 and 1895 were marked by violent Hindu-Muslim riots in Bombay and the United Provinces. These events, widely reported in nationalist newspapers like Kesari—edited by Bal Gangadhar Tilak—left a lasting impression on the young Savarkar. Reading about the violence and what he perceived as the repeated humiliation of Hindus, he began to internalize a narrative of historical wrongs and a deep concern about the disunity and passivity of the Hindu community.

According to biographer Dhananjay Keer, these events “fired his blood,” and young Savarkar resolved to take retaliatory action in his own small way. The target of his symbolic protest was a disused mosque in his hometown of Bhagur.

The Mosque Incident

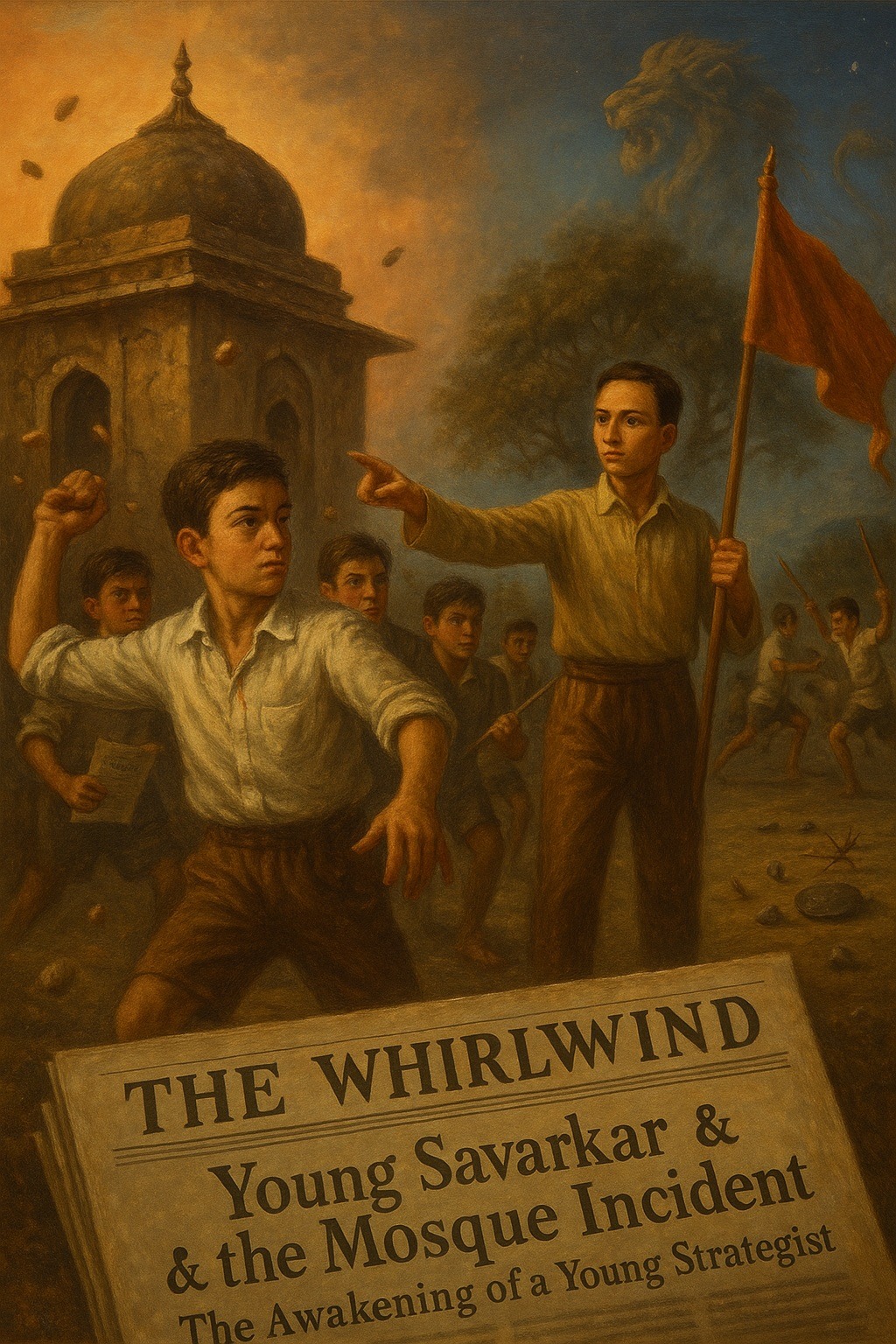

Savarkar, then still a schoolboy, organized a small group of like-minded friends and led them in an attack on the mosque. Armed with stones and sticks, they damaged the windows and roof tiles of the building. It was a calculated act, carried out at dusk, and the group quickly dispersed afterward. The action was seen, at least by the participants, as a form of symbolic retaliation for the attacks on Hindus during the riots.

The news of the attack soon reached the local Muslim boys, and a confrontation ensued at school. A skirmish broke out between the two groups. Savarkar, described in later accounts as the “Hindu Generalissimo,” led his group using makeshift weapons such as penknives, pins, and even thorns. Despite being temporarily outnumbered, his group emerged victorious. A temporary truce was reached between the sides, agreeing not to report the matter to school authorities. However, the episode left a lingering tension—some Muslim boys reportedly sought revenge by threatening to desecrate Savarkar’s Brahmin identity by forcing meat into his mouth.

Mock Battles and Early Militarization

Far from treating the incident as an isolated act, Savarkar later reflected on it as a formative experience. He recognized, even at that young age, that the Hindu community’s internal divisions—especially along caste lines—made it vulnerable to external aggression. He also perceived a lack of organized response and group cohesion among Hindus.

In response, Savarkar began what he called a kind of “military training” among his peers. He divided his friends into two mock battalions—Hindus versus Muslims or the British—and organized simulated battles in open fields using neem seeds as bullets. At the center of each battlefield stood a saffron bhagwa flag. Victory was declared when one side captured the opponent’s weapons and flag. Almost always, the Hindu side, led by Savarkar, emerged victorious. When the opposition appeared close to winning, Savarkar reportedly persuaded them to concede for the sake of the “national interest.”

These sessions were followed by celebratory processions through the streets of Bhagur, singing victory songs. The activities were more than just child’s play—they reflected an emerging ideology centered around pride, resistance, and martial organization.

Interpretation and Legacy

The Bhagur mosque incident and the mock battles that followed have been interpreted in multiple ways. Supporters of Savarkar view these acts as early signs of his courage, leadership, and commitment to collective Hindu strength. To them, the incident symbolizes the awakening of a political consciousness that would later fuel his vision of Hindu unity and national self-assertion.

Critics, however, point to the same episode as an early indication of Savarkar’s communal worldview. They argue that his actions reflected a sectarian understanding of Indian society, one that would later be formalized in his theory of Hindutva, which framed Hindus and Muslims as fundamentally distinct and politically incompatible communities.

What is clear is that the Bhagur incident was not an organized communal campaign but a one-time, youthful episode shaped by the immediate historical context. Nonetheless, it played a significant role in shaping Savarkar’s emerging worldview—one that emphasized unity, discipline, resistance, and the need for a martial spirit among Hindus.

Final Thoughts

The story of the Bhagur mosque incident is not just a tale of youthful rebellion; it is a window into the formation of one of modern India’s most controversial political actor and thinker. Whether viewed as an act of symbolic resistance or as an early sign of sectarian antagonism, the episode remains a significant moment in understanding how Savarkar began to see the world—and how he would later seek to change it.

Do you see Savarkar’s actions in Bhagur as youthful rebellion or as the seed of a larger ideology? How should we evaluate symbolic acts of resistance carried out in times of communal tension? Can childhood experiences like the Bhagur incident shape an entire political worldview? If you were a contemporary of young Savarkar, how might you have reacted to his actions in Bhagur? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

KEER, Dhananjay. Veer Savarkar. Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1966.

SAMPATH, Vikram. Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1883–1924. Gurgaon: Penguin Viking, 2019.

Leave a Reply