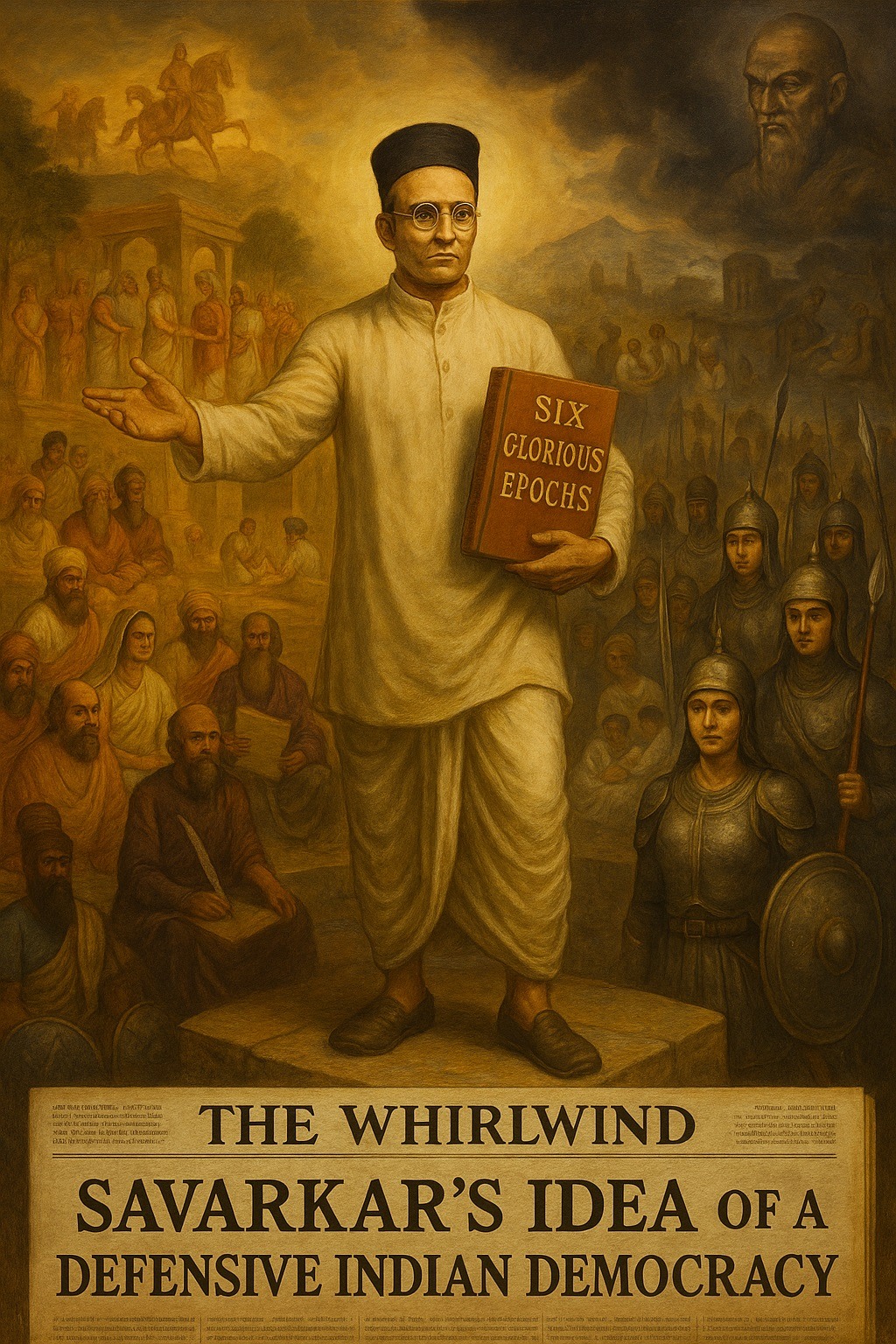

Political Dimension of Hindutva, Part 8

The political ideas of Vinayak (Veer) Damodar Savarkar cannot be clearly assigned to a specific model of governance. However, with the transformation of British India into the independent Indian Union, democratic concepts increasingly became the focus of his thinking. In his final work, Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History, he describes a form of democracy that he refers to as “Defensive Indian democracy.” He bases this concept on historical republics (Ganas) and city-states (Janapadas) in the Indian subcontinent that developed resilience against external aggressors.

Characteristics of Defensive Indian Democracy

Democratic Constitutions

Savarkar emphasizes that these early Indian republics were democratically organized. He cites the Greek historian Diodorus, who describes their governmental structures as “excellent.” These societies had laws that ensured order and prosperity (see reference to Diadorus in Savarkar SGE 1971:16).

Promotion of Physical Strength and State Control

A central feature, according to Savarkar, was the deliberate promotion of physical strength among citizens to ensure military readiness. The state actively intervened in individual freedoms to maintain the quality of the population. He describes a form of state-controlled birth policy, even involving the selection of offspring. Marriages were not arranged based on financial interests but on the physical fitness, beauty, and health of the partners. Additionally, newborns underwent medical examinations, and if incurable diseases or natural defects were detected, state-ordered euthanasia was carried out—a practice Savarkar compares to Spartan policies.

Militarization and Universal Conscription

Many of these republics, particularly in India’s northern border regions, were heavily militarized. Military service was mandatory not only for men but also for women. In times of war, the entire population could be mobilized for defense. Savarkar describes the Youdheya Republic as “a nation in arms.”

Valor and Honor as Virtues

These early Indian democracies were characterized by a strong sense of virtue, particularly in the Malava and Shudrak republics. These states were willing to set aside internal conflicts to defend themselves against external threats. In this context, Savarkar describes mass inter-caste marriages as a social reform measure aimed at creating a unified political and social community in order to build a joint combined military force.

Resistance to Foreign Rule

Despite the temporary necessity of uniting smaller states, these republics strongly opposed any form of foreign domination. Within a few months of the arrival of Greek occupiers, all Greek power structures on the Indian subcontinent were eradicated.

National Unity and Vedic Identity

Another key element was the deep connection of these republics to Vedic religion and a strong national consciousness. Particularly, Kalinga and Andhra considered it their duty to repel foreign aggressors when other Indian states were unable to do so. Savarkar views this as an expression of collective national solidarity.

The Role of Kautilya and Centralization

Savarkar refers to the ancient Indian strategist Kautilya (Chanakya), whose political theory stated that martial spirit and military strength were the foundations of any functioning society. For Savarkar, this was the core principle of a “Defensive Indian democracy,” which put him in direct opposition to the philosophy of non-violence (Ahimsa), especially in relation to Buddhism. However, with regard to “defensiveness” it can be concluded that for Savarkar there was no question that this was a characteristic that was generally common to all Indian states of that time. Regardless of whether they had a democratic constitution or not, i.e. whether they were part of the Rajakas (monarchies) or the Prajakas (republics).

He further argues that smaller republics had to sacrifice their democratic ideals in times of national danger to follow a stronger, centralized leadership. He compares the Indian city-states to Greek ones and highlights the necessity of a unifying leader—similar to Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great—to consolidate a fragmented nation. In this context, he sees the Marathas as the force that should lead India into a strong unity, just as the Gupta emperors had begun in ancient times.

Final Thoughts: The Idea of a Defensive Indian Democracy

Savarkar’s concept of a “Defensive Indian Democracy” combines democratic principles with military strength, social control, and nationalist unity. While he acknowledges the early city-states, he considers them only a transitional phase toward establishing a centralized and powerful Indian state. For him, history’s lesson is clear: only a united, militarily strong nation can resist external enemies and maintain its independence.

His ideas remain controversial, as they integrate authoritarian tendencies into democratic structures and propose radical forms of social control. Nevertheless, his concept of a “Defensive Indian Democracy” remains an important part of the political discourse on India’s past and future.

What do you think Savarkar meant by a “Defensive Indian Democracy”? How do you interpret the balance between democracy and militarization in his model? Do you see similarities between Savarkar’s ideas and modern notions of national security? Could Savarkar’s emphasis on military readiness be relevant in today’s globalized, nuclear-armed world? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1970. The Indian war of Independence 1857. Rajadhani Granthagar: New Delhi.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1971. Six glorious (golden) epochs of Indian history. Savarkar Sadan: Bombay. 1971.

Leave a Reply