Savarkar’s Philosophy & Worldview , Part 7; Savarkar’s Agnosticism, (3/4)

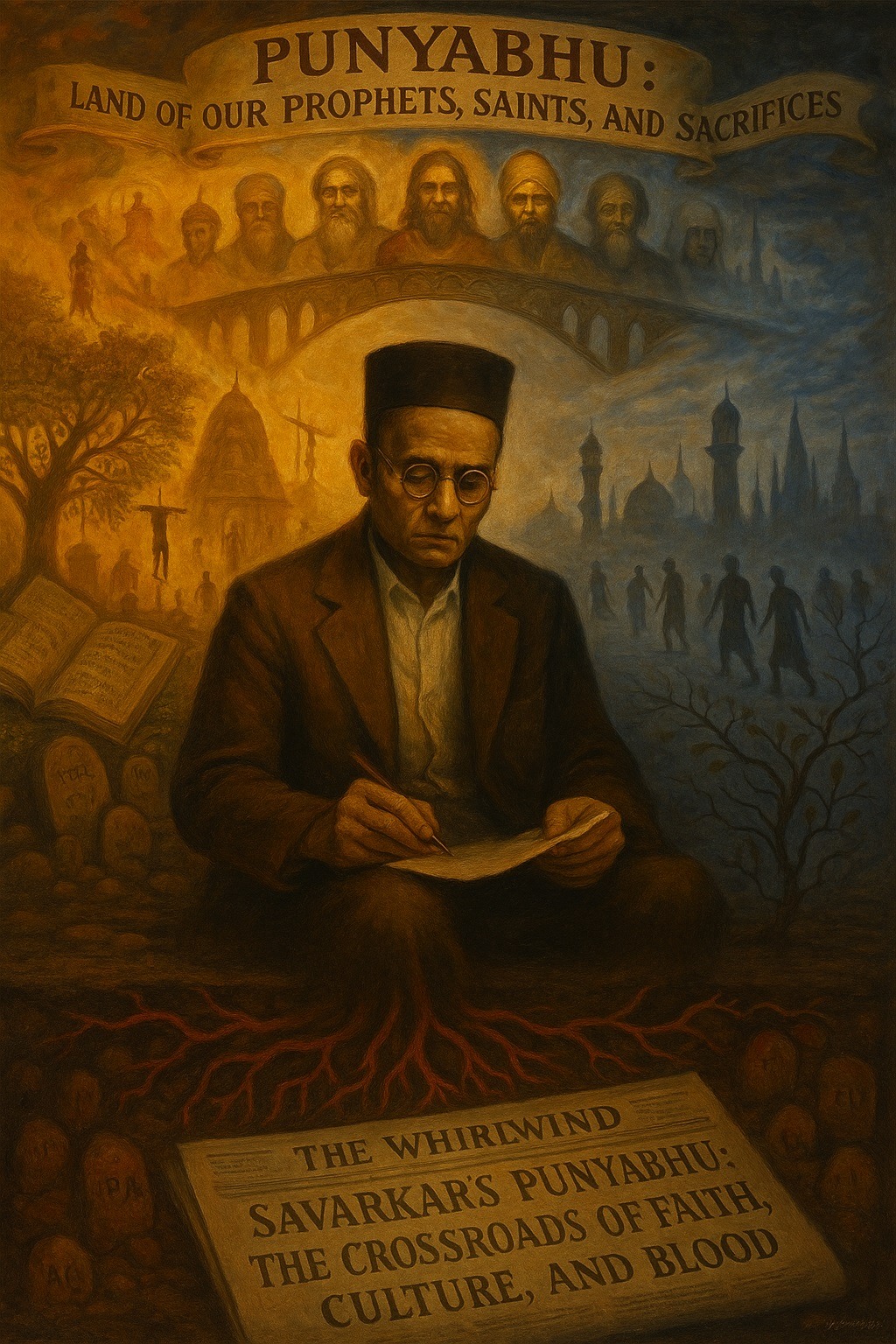

In the ongoing exploration of Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar’s agnosticism, one of the most intriguing and misunderstood concepts is his use of the term Punyabhu or Punyabhumi, often translated as “Holy Land.” This term has sparked significant debate, with both critics and supporters often misinterpreting its meaning. For Savarkar, Punyabhu was not merely a religious construct but a deeply patriotic and cultural one, tied to his vision of Hindutva and the idea of a Hindu Rashtra. This blog post delves into the nuances of Savarkar’s interpretation of Punyabhu, its implications, and the challenges it presents in understanding his worldview.

Punyabhu: Beyond Religious Merit

Traditionally, Punyabhu is understood as a land where one can acquire religious merit through good deeds or spiritual practices. However, Savarkar redefined this concept in a way that emphasized patriotism and cultural identity over religious devotion. For him, Punyabhu was not just a land of pilgrimage or piety but a land of heroes, martyrs, and shared heritage. He described it as the land of [his] prophets and seers, of his saints and gurus, the land of piety and pilgrimages. Yet, he also emphasized that it was a land where every stone here can tell a story of martyrdom!

This duality reveals Savarkar’s attempt to frame Punyabhu as a cultural and civilizational concept rather than a purely religious one. He associated it with Sanskriti, the collective expression of Hindu civilization, encompassing literature, art, history, social institutions, and even festivals and rituals. While these elements often carry religious connotations, Savarkar insisted that they were part of a shared national heritage rather than a specific faith.

The Challenge of Separating Religion from Culture

Despite Savarkar’s efforts to secularize the concept of Punyabhu, the religious undertones are hard to ignore. Terms like “rites,” “rituals,” “ceremonies,” and “sacraments” inherently evoke religious imagery. Savarkar was aware of this tension and clarified that his interpretation was an individual perspective, not tied to any religious institution or dogma. He emphasized that Punyabhu represented a “common heritage” on a national level, transcending religious boundaries.

However, this attempt to disentangle culture from religion creates a continuum of interpretations, ranging from contextual to literal understandings of Punyabhu. This continuum is crucial because it shapes how Savarkar’s vision of a Hindu Rashtra would accommodate or exclude different religious communities.

Contextual vs. Literal Interpretations

The contextual interpretation of Punyabhu focuses on patriotism and cultural assimilation. According to this view, non-Hindus could claim India as their Punyabhu if they embraced Sanskriti and demonstrated Desabhakti—undivided love for the homeland. Savarkar argued that loyalty to the nation could be proven through participation in cultural practices, even if one did not adopt all Hindu traditions.

In contrast, the literal interpretation insists that India must be the “holiest land” for all its inhabitants, with their most sacred sites located within its borders. This interpretation excludes followers of non-indigenous religions like Islam and Christianity, whose holiest places—Mecca, Bethlehem, or Rome—lie outside India. Savarkar’s controversial statement that “their love is divided” reflects this mistrust of the loyalty of non-Hindus, making it difficult for them to claim India as their Punyabhu.

A Middle Ground: The Extended Literal Interpretation

Between these two extremes lies a third approach, which should be called here as the “extended literal interpretation,” which combines elements of both contextual and literal understandings. This interpretation allows for the inclusion of non-Hindus if their “important holy places” are located in India. It emphasizes patriotism and loyalty as the primary criteria for belonging, while still acknowledging the significance of religious sites.

This approach introduces a counterforce to the exclusionary tendencies of the literal interpretation, offering a pathway for non-Hindus to prove their Desabhakti and integrate into Hindu society. However, it still relies heavily on religious markers, highlighting the inherent tension in Savarkar’s attempt to secularize Punyabhu.

Strategic Agnosticism and Political Mobilization

Savarkar’s use of religious language to define Punyabhu reveals a strategic approach to politics. While he claimed that his concepts of Hindutva and Punyabhu had little to do with agnosticism or atheism, his rational and pragmatic use of religious imagery suggests a form of “strategic agnosticism.” As Matthew Lederle puts it, this approach allows for the mobilization of diverse groups under a unified national identity, regardless of their individual beliefs.

Savarkar’s famous statement—”Some of us are monists, some pantheists, some theists, and some are atheists. But whether monotheists or atheists, we are all Hindus and share a common blood” (Savarkar 1999:56)—encapsulates this inclusive yet strategic vision. It underscores his belief in a shared cultural and civilizational identity that transcends religious differences, even as it leverages religious symbolism for political purposes.

Final Thoughts: The Legacy of Punyabhu

Savarkar’s concept of Punyabhu remains a complex and contested idea, reflecting the challenges of separating culture from religion in the context of nationalism. While his attempt to redefine Punyabhu as a patriotic and cultural construct is innovative, it is not without contradictions. The continuum of interpretations—from contextual to literal—highlights the difficulty of applying this concept in a diverse and pluralistic society.

Ultimately, Savarkar’s use of Punyabhu reveals his willingness to employ religious language as a tool for political mobilization, even as he sought to distance himself from religious dogma. This strategic agnosticism underscores the pragmatic nature of his vision for Hindutva and the Hindu Rashtra, leaving a legacy that continues to provoke debate and reflection.

What do you think about Savarkar’s interpretation of Punyabhu? Does it succeed in bridging the gap between religion and patriotism, or does it fall short in addressing the complexities of India’s diverse cultural landscape? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Sources:

KLIMKEIT, Hans-Joachim. 1981. Der politische Hinduismus. Indische Denker zwischen religiöser Reform und politischen Erwachen. Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden.

LEDERLE, Matthew. 1976. Philosophical Trends in Modern Maharashtra. Popular Prakashan: Bombay (Mumbai).

ROTHERMUND, Dietmar. 2003. „Asien und die Globalisierung in historischer Perspektive“. Referat im Rahmen der Tagung: Asien in der Globalisierung Weingartener Asiengespräche 2003. Akademie der Diözese Rottenburg-Stuttgart, Weingarten/Oberschwaben, 31.1.-2.2.2003

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1999. Hindutva: Who is a Hindu. Seventh Edition. Swatantryaveer Savarkar Rashtriya Smarak: Mumbai.

SAVARKAR, Vinayak Damodar. 1909. O’Martyrs. India House: London.

Leave a Reply